A pitched battle over a journalist, a traffic light, and cutting and sewing: this is how World Cup cards were born.

Kenneth George Aston , known as Ken Aston in the world of football, was a prominent referee in the middle of the last century. A restless and innovative man, he would leave as a legacy the invention of the yellow and red cards, to simplify the work of his successors. He was English, from Colchester, Essex, a teacher and a lieutenant colonel in the Army on leave. His is an interesting biography. He graduated from Saint Luke's College in Exeter, which must have been something because Stanley Rous , a famous referee from the beginning of the last century, a man who gave a definitive form (up to his present-day antics) to the Rules and became president of FIFA, and George Reader , referee in the 1950 Brazil final, the Maracanazo.

Aston began refereeing in 1936, in the lower categories and as a linesman until the war dictated otherwise. At 21, he wanted to join the RAF, where he was rejected due to an ankle problem. He joined the Royal Artillery, incorporated into the British Indian Army, and was forced to fight the war in Southeast Asia. He reached the rank of lieutenant colonel and at the end of the war, given his personality and training, he was integrated into the Changi War Crimes Tribunal , the replica of the Nuremberg Trials in the town of Changi, Singapore, for crimes against humanity in the Pacific. Upon his return, in 1946, he resumed his refereeing activity and began working as a teacher, which would be his profession for the rest of his life, although he remained a lieutenant colonel in the reserve.

He was a good referee, tall, with an elongated head and such large, open ears that they could have inspired the trophy for the winner of the European Cup in its 1967 design, the popular "big-eared" one. He recommended, and was listened to, replacing the linesmen's flags, which until then had been provided by the local team in their own colors, with red and yellow ones, more visible on foggy London afternoons. He replaced the old jacket with a more comfortable garment, also equipped with pockets for his whistle and notebook, with a military-inspired design. In 1953, he reached the First Division, while also reaching the rank of head of studies at Newbury Park Primary School in Ilford, Essex, where he settled.

Respected, authoritative, with a thorough understanding of, and a perfect understanding of, the XIV Rules, he achieved international acclaim. In 1960, he was entrusted with the second leg of the first Intercontinental Cup, Real Madrid-Peñarol, which the Whites won 5-1 in the greatest occasion he had ever experienced, and perhaps will ever experience, at the Bernabéu Stadium. He also officiated numerous European Cup, Cup Winners' Cup, and Fairs Cup matches outside his home country, noting that the customs and practices of continental football were different from those in his home country, where players did not seek to deceive and the public scrupulously respected refereeing decisions. The newspapers followed a similar line, where the referee's name was placed at the foot of the lineups without comment.

But nothing compared to what he experienced in the 1962 World Cup in Chile, where circumstances placed him in front of the most difficult match ever to referee. Weeks before the tournament, two Italian journalists were sent to Chile to report on that country, unknown to Italians. Let's just say they weren't very cautious when it came to expressing their impressions. Corrado Pizzinelli 's report for the Bolognese newspaper Il Resto del Carlino was top-notch. It was titled "Santiago, the End of the World," and the subtitle was "The Infinite Sadness of the Chilean Capital," and it portrayed it as a sad, hopeless country, lacking vitality, "with entire neighborhoods given over to open-air prostitution." He describes it as "a 3,500-kilometer-long strip that begins at the edge of the desert and ends to the south with the ice of the Pole, with the ocean to the west and the Andes mountain range to the east, which separate it, like the desert and the Pole, from the rest of the world."

The article was picked up by an international news agency and published by El Mercurio, the country's most important newspaper. The outrage was tremendous. Chile had made a tremendous effort, even overcoming a destructive earthquake in May 1960 that left more than two million people homeless, to have everything ready to host a World Cup that was conceived as Chile's entry into the international community as a progressive country. And now an Italian journalist came along with these...

The worst part was that Italy and Chile were drawn together in the draw, destined to play each other on the second matchday. The Azzurri were always surrounded by maximum protection from the Army, both in the hotel and on their trips to training and to play matches. In the first, against Germany, they had the crowd radically against them, but they ended up with a 0-0 draw. Chile, on the other hand, defeated Switzerland 3-1. On June 2, the host country and the unwanted visitor faced each other in Santiago de Chile. Frenchman Robert Vergne would write this in his Golden Book on the World Cup: "The Chile-Italy match will remain in the annals and in the memory of those who saw it as the typical example of an affronting, horrific, even unbearable match. The incidents, grabbing, and ill-advised blows constituted the essence of the match, under the watchful eye of a lamentable English referee, Mr. Aston."

Admonitions fall on deaf earsThe heat on the eve of the match was such that, despite a decent draw against Germany, Italy substituted six players simply because they didn't dare come off. Chile hit terribly, encouraged by their fans, Italy responded by having brought off the bravest players, and Aston, overwhelmed, only dared to send off two Italians (the first refused to come off and had to ask the police to remove him), leaving the eleven Chileans on the field, including Leonel Sánchez after he punched Mario David in the style of a boxing star. Of course, none of the players knew English, nor did Aston know Spanish or Italian, so their admonitions fell on deaf ears. For the first time, he felt powerless, in need of some lifeline to reinforce his authority.

That discouraged him, and his refereeing career ended. He only stayed for one more year, in England, and bid farewell with honors by officiating the 1963 FA Cup final between Leicester and Manchester United. It wasn't just any final: that year marked the centenary of the birth of football and the creation of the Football Association. A solemn occasion, a fitting farewell.

For the next World Cup, England 1966, he chaired the Refereeing Committee, as the person ultimately responsible for selection, instructions, and appointments. He obviously witnessed the famous England-Argentina match in which the German Kreitlein sent off Rattín , the Argentine captain. Rattín later explained it this way: "That guy charged us for everything, and they didn't even call a foul. I protested, and they ignored me. I showed him my armband, asked for an interpreter, insisted, and then they started making gestures for me to leave." Aston himself, the Argentine coach Toto Lorenzo, and some Bobby had to go to the center of the field to remove him. This created a stir. Rattín sat defiantly on the red carpet leading to the box. When he was marched into the locker room, he contemptuously twisted the corner flag, which displayed the Union Jack.

The next day he was in his office at Wembley when Jackie Charlton called. A newspaper had reported that he and his brother Bobby had been warned of expulsion. They didn't know it and wanted to certify it. Combining the two cases, that of Rattín and that of the Charlton brothers, with the memory of the Battle of Santiago de Compostela, Aston began to think about the need to create an easy, international, unequivocal system so that players cautioned by the referee would know. And so would spectators, so that there would be no doubt. Stopped at a traffic light in Kensington, he thought: "It should be as clear as this: yellow, caution; red, no entry... But how? If it were as easy as putting a traffic light with lights on the pitch...!" He arrived home and shared his concern with his wife, Hilda , who seemed not to hear him, attentive as she was to her employers, since she was a fan of dressmaking magazines. Then he began to read the newspaper. A little while later, Hilda appeared before him. He had cut out two pieces of cardboard, one yellow and one red, and showed them to him: "What if referees carried two of these in their pockets? The yellow one for a warning and the red one for a sending-off."

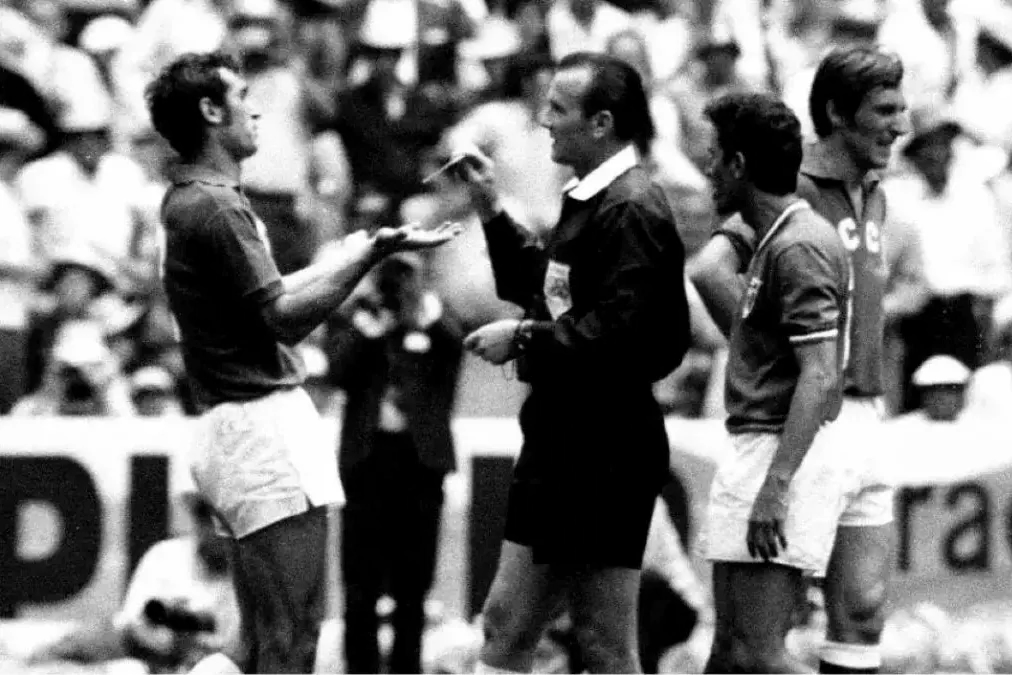

Aston was happy with the idea, and after much discussion and some rehearsals, it was fully operational at the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. The first attempt came in the opening match, Mexico vs. USSR, on May 31, 1970. The German Tschenscher showed it to the Soviet Asatiani for a harsh tackle on local player Velarde in the 27th minute. The first cautioned player would die violently at the age of 55 in Tbilisi. For a time, director of the Georgian Sports Department, he went into business and was machine-gunned by two unknown assailants waiting for him in a car after a meeting. They never showed up. One of many crimes in the upheavals that followed the dissolution of the USSR.

Quini's protestsThe first red card in a World Cup (not the first expulsion, as it had already happened in 1930, the inaugural one) didn't come until the next one, Germany 1974, and it was seen by Chilean Carlos Caszely , famous for his gallantry when he denied Pinochet a handball. He was then playing for Levante, who had recently been relegated to the Third Division. Our well-known Babacan showed it to him for rebelling against the harshness of his marker, Vogts . He felt it was unfair.

They arrived in Spain with the 1970-1971 season already underway, on January 15, 1971. The yellow jersey was changed to white at the idea of the Federation's secretary, Andrés Ramírez , who feared that on our old black and white televisions the yellow ones could be confused with the red ones. The first one was seen in Spain by the great Quini playing for Sporting, for protesting against the Mallorcan Balaguer , and the first two red ones, simultaneously, were shown by Orrantía to the Sporting player Lavandera and the Celta player Hidalgo for fighting. The white jersey lasted here until 1976-1977, when the television park was considered renovated.

As for Ken Aston, it was also his idea to introduce the fourth official, who would act as a substitute in the event of an injury to any of the starting three, and the numbered board for substitutions. He played a prominent role as an instructor and trainer of referees in the United States, when football was first taking off there, and died in 2001, aged 86. Four years earlier, he had been awarded a Member of the Order of the British Empire. He left his mark on the short history of football, which he defined as "a play in two acts with 22 actors and a stage manager, the referee."

elmundo