China in chronic jet lag

China geographically stretches over an area of over 5,000 km, which would naturally translate into five time zones. However, immediately after the proclamation of the People's Republic of China, the so-called New China, in 1949, the decision was made to establish a single time zone, known as "Beijing Time" or China Standard Time (CST), which is eight hours ahead of universal time year-round (UTC+8; this time is 6 hours ahead of summer time in Poland and 7 hours ahead of winter time).

The communist authorities then abolished the five-time-zone system (UTC+5:30 to UTC+8:30), previously introduced by the Government of the Republic of China. This was a conscious political act.

The unification of time was intended to be a powerful symbol of national unity and the centralization of power in Beijing. The slogan "one China, one time zone" became the foundation for the construction of a new, centralized state in which the clock, like language and currency, was to unite the vast territory.

Today, the consequences of this decision are most felt in the West. In regions like Xinjiang and Tibet, where natural solar time lags two or even three hours behind Beijing, daily life unfolds in a kind of dualism. Official work hours, such as 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., effectively mean working in the morning darkness and a constant conflict between the internal biological clock , synchronized by sunlight, and the social clock imposed by the administration.

China's Chronic Social Jet LagScientists call this phenomenon chronic "social jet lag." Scientific studies published in the journal "Sleep Medicine," among others, provide evidence of its harmful effects. An analysis of data from 31 Chinese provinces found that geographic location within a single time zone explains 15-18 percent of the variability in life expectancy, with a distinct disadvantage for Westerners. Other studies correlate persistent circadian rhythm misalignment with an increased risk of depression and obesity.

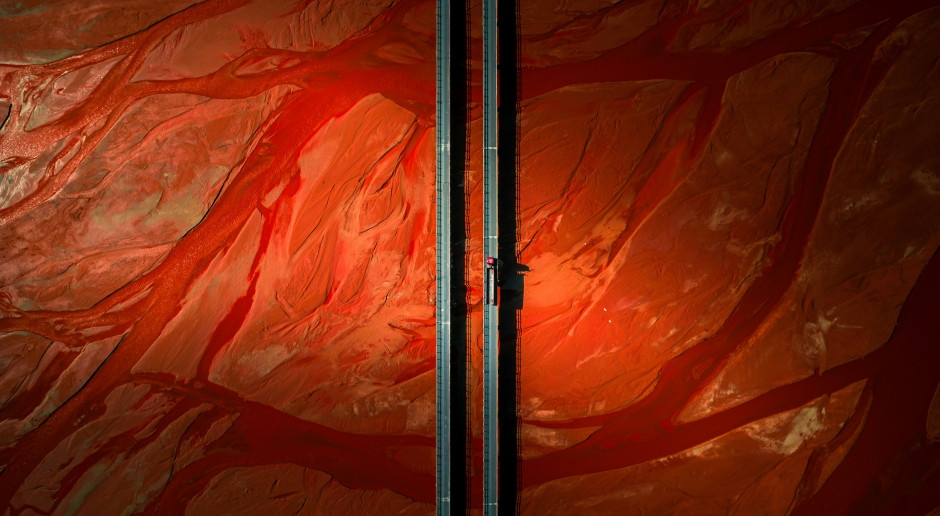

China and social jet lag Photo. Nuno Alberto / Unsplash

China and social jet lag Photo. Nuno Alberto / UnsplashTo cope with this uncomfortable situation, residents of the western regions, especially Xinjiang, have developed a dual time system. Beijing time applies to official matters, train stations, and airports. However, in everyday life, in conversations, and in local markets, the unofficial "Xinjiang time" prevails, offset by two hours (UTC+6). However, when saying "let's meet at two," one must always confirm the time.

Local businesses and government offices in Xinjiang also often operate from 10am to 7pm Beijing time, which corresponds to the more natural hours of 8am to 5pm local solar time.

For the Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim minority , using local time has also become a form of silent resistance and a manifestation of cultural distinctiveness against Beijing's domination.

However, it should be remembered that approximately 6% of the population lives in the west of China, while the remaining 94% is concentrated in the eastern part.

A single official zone and local time duality also create economic and practical challenges.

One time zone and economic problemsCompanies operating nationwide struggle to coordinate work between east and west. While Shanghai offices close at 5 p.m., the sun is still high in Kashgar, and the local workday is in full swing.

Deloitte and KPMG reports point out that managing east-west operations and meetings is inefficient, which poses a constant productivity challenge for national companies.

Significantly, China also experimented with daylight saving time between 1986 and 1991, primarily to save electricity. According to official estimates , the benefits were measurable but modest. For example, in 1986, it resulted in an estimated 700 million kilowatt-hours of savings. However, Chinese authorities deemed the administrative and logistical costs of the changes, particularly the conflicting schedules for flights, trains, and buses , too high for a centralized government.

This decision demonstrates the priorities of an authoritarian state: control and stability are more valuable than economic optimization.

For Europe, the Chinese lesson, although it is an extreme example, is clear: giving up daylight saving time is one thing, but the key is what fixed time is chosen.

Establishing a standard that permanently disconnects daily life from the natural day-night cycle carries tangible health, social, and economic costs that China has been experiencing for decades.

From Beijing Krzysztof Pawliszak.