How a Mexican cartel built a fuel smuggling empire using ships

On the afternoon of March 8, an oil tanker named Torm Agnes entered the Port of Ensenada , on Mexico's Pacific coast, carrying nearly 120,000 barrels of diesel.

Such a vessel was unusual in that port, which primarily handles cruise ships, luxury yachts, and container ships. Ensenada lacks the infrastructure necessary to safely unload flammable hydrocarbons , making it even more unusual.

Waves of trucks arrived at the dock to take away much of the cargo from the Torm Agnes.

Workers rushed to fill the vehicles' tanks, up to six at a time, using hoses extending from a larger one attached to the vessel. The operation, although risky, was carried out with precision, according to an eyewitness and a photo and video of the incident shared with Reuters.

"They had a team, they were very meticulous in what they had to do, and they were very fast," the person said. "They worked nonstop, even at night."

The audacious maneuver was the work of cartel-linked smugglers, according to three Mexican security sources and three people familiar with the operation, part of a wave of smugglers revolutionizing Mexico's fuel market with a flood of low-priced fuel obtained primarily from the United States and disguised in customs declarations as something else.

Mexican criminals didn't act alone. A Houston company called Ikon Midstream played a key role in the multi-million-dollar Ensenada operation, Reuters discovered.

He purchased the diesel in Canada, claimed in the documentation that it was lubricant , and chartered the vessel to deliver it to a client who, according to Mexican authorities, is a front for one of the country's largest and most violent cartels.

Ikon Midstream and its chief executive, Rhett Kenagy, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Attorney Joseph O. Slovacek, who represents the company and Kenagy, told Reuters in an October 18 email to stop contacting his clients. "No one will talk to your reporter!" Slovacek said.

The Port of Ensenada did not respond to a request for comment. Denmark-based Torm, which operates one of the world's largest tanker fleets, including the Torm Agnes, said it stopped operating with Ikon Midstream a few weeks after the Ensenada incident.

Narcotics remain the main source of income for Mexican cartels. However, illegal fuel and stolen crude oil have become the largest source of non-drug revenue for these criminals, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Drug traffickers have built this lucrative secondary business by effectively integrating into the vast North American energy sector and dominating the logistics of transporting petroleum products by truck, rail, and, recently, by ship.

Some U.S. officials have begun calling ships carrying illegal fuel a new "dark fleet," a term most often associated with the illicit transport of Russian or Iranian crude oil designed to evade sanctions.

Fuel smuggling has grown so rapidly that illegal imports now account for up to a third of Mexico's diesel and gasoline market, taking profits away from some of the largest oil companies, five current and former government sources told Reuters.

The illegal fuel entering the country is valued at more than $20 billion a year, according to one of the people who helped the Mexican government calculate the scale of this illicit trafficking.

Law enforcement on both sides of the border are alarmed. The U.S. government is offering rewards of up to $10 million for information on crimes related to cartel fuel.

In Mexico, ship smuggling has sparked a corruption scandal that is now rocking the country's Navy, the entity that manages ports and has long been considered one of the country's most trusted institutions.

At a press conference on September 7, Navy Secretary Raymundo Morales stated that the institution had launched an internal investigation and that "we will not tolerate corruption under any circumstances."

To unravel the ins and outs of fuel smuggling into Mexico—known locally as huachicol fiscal—Reuters interviewed more than 50 people with knowledge of the matter, including five people with experience in illicit shipments, Mexican and U.S. law enforcement officials, current and former oil industry executives in both countries, as well as oil product marketers and regulatory compliance specialists.

Many of these people spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of their safety.

Reuters is the first agency to publish a complete account of the Torm Agnes's voyage, from its embarkation in Canada to its unloading in Ensenada and another Mexican port, from which it hastily withdrew.

The account is based on information from seven people , all involved in the logistics of the cargo transfer or investigating the consequences of the voyage, as well as vessel tracking data and satellite imagery, internal shipping documents, customs data, and port records.

Through these documents and sources, Reuters reconstructed in never-before-reported detail how the alleged scheme operates and exploits loopholes in the vast and complex U.S. energy sector, affecting a range of entities, including major oil companies, shipping companies, and government agencies.

According to authorities, the cartels rely on the help of U.S. actors who facilitate the acquisition and transportation of products, some unknowingly, others actively participating. Texas State Senator Juan Hinojosa said his oil-rich state has become a hotbed for suspicious operators.

"Cartels have infiltrated many legitimate businesses along the border and further north," added Hinojosa, a Democrat who in March sponsored legislation seeking to crack down on unlicensed fuel depots near the border, tighten regulations for fuel transporters, and increase penalties for those who break the law. The bill is stalled in the Texas Senate but could be revived in the future.

The fuel smuggling scheme largely boils down to lucrative tax evasion. Mexico applies a tax known as IEPS (Income Tax on Fuel) to various products, including imported diesel and gasoline.

Mexico is a major producer of crude oil , but it imports these fuels because its aging refineries cannot meet local demand. Criminals evade the tax, which is levied per liter and often amounts to more than 50% of the cargo's value, by claiming that foreign fuel is just another type of petroleum product exempt from the tax.

U.S. and Mexican officials say smugglers often use shell companies and falsified shipping documents to cover their tracks, and pay bribes to corrupt port and customs officials to get their cargo through.

They also unload quickly in dangerous locations, bypassing Mexico's nearly two dozen maritime facilities designated for the safe unloading of fuel, according to authorities and industry experts. This allows smugglers to deliver illegal fuel to their customers quickly , with minimal oversight and regulation.

Smuggled diesel is sold at a discount on the Mexican market to thousands of unlicensed gas stations, factories, and mines. Smuggled proceeds are primarily destined for unbranded gas stations.

The cartels also steal fuel and crude oil directly from Pemex and sell a portion of it in the United States, with the help of corrupt importers who are selling at lower prices than U.S. producers, according to the U.S. Treasury Department.

Pemex did not respond to a request for comment on losses related to fuel theft and smuggling.

Other oil companies are also suffering the consequences. In May, the British multinational Shell confirmed the sale of its fuel retail business in Mexico. This exit was due in part to difficulties competing with cheaper drug fuel, five Shell sources told Reuters. Gas stations buy contraband fuel at a discount of between 5% and 10% off the price of legitimate imports, according to two sources familiar with the sector.

Shell declined to comment on the reasons for the sale.

The Torm Agnes was carrying diesel it had picked up in Canada at the beginning of its journey to Mexico, the seven sources familiar with the matter told Reuters. By the time the vessel arrived in Ensenada, its cargo had been transformed, at least on paper, into a petrochemical used to make industrial lubricants, according to cargo documents and port records reviewed by the news agency.

If that diesel, valued at approximately $12 million, had been declared to customs authorities, it would have been subject to nearly $7 million in taxes upon entering Mexico, according to a Reuters calculation based on the volume of diesel and the tax rate in effect at the time. However, the petrochemical was exempt from the tax.

The Danish-flagged Torm Agnes was one of several tankers that transported fuel in recent years but declared their cargo as lubricants to evade taxes and customs controls, according to an undated summary of the alleged smuggling scheme compiled by government security forces and seen by Reuters. The authenticity of the memo was confirmed by two security sources.

The Mexican government has not said how much fuel smuggling has cost the country in lost IEPS revenue, but the source who used to help the treasury calculate the size of the illicit trade said it was nearly $4 billion in 2024. The opposition PAN party has raised the figure even higher, to around $10 billion, calling it "the largest act of corruption in the history of Mexico."

Neither Mexico's tax authority nor its customs agency responded to requests for comment.

The American ConnectionAt the center of that deal was a U.S. company: Ikon Midstream, a Houston-based fuel marketer. The company bought the Canadian diesel and contracted Torm Agnes to deliver it to Mexico, according to four of the people and internal Ikon Midstream documents obtained by Reuters.

In addition to the shipment to Ensenada, Ikon Midstream has arranged at least four other ocean-going diesel deliveries to Mexico this year, Reuters has learned.

Between January 8 and March 4, the company used a different tanker from the same fleet, the Torm Louise, on four separate occasions to transport cargo from Texas to the Port of Tampico on the Gulf of Mexico coast, according to tanker tracking data and the shipping company Torm, which manages the Torm Agnes and Torm Louise.

Torm told Reuters that both vessels were loaded with diesel. He added that the Torm Louise also transported naphtha on three of its voyages. In Mexico, smugglers often use this highly flammable hydrocarbon to make low-quality gasoline.

However, in their declarations to Mexican customs, the five shipments were declared as "lubricant additives" not subject to the IEPS (Tax Excise Tax), according to Mexican port records obtained by Reuters through transparency requests.

The product declared on the U.S. export bills of lading for two of the Torm Louise shipments was also lubricants, according to Kpler, a Brussels-based maritime data provider.

Reuters is the first to report that Ikon Midstream labeled these diesel shipments as lubricants in U.S. customs declarations.

Kpler said it was unable to share the source documents due to confidentiality agreements with its data providers.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which maintains copies of these documents, initially rejected a Reuters access to information request for them in June.

In October, CBP stated that the information requested by Reuters was available on physical cargo manifests that must be requested in person at each port of export, a process the agency described as "excessively lengthy" and subject to further delays.

Torm, in an August 5 email, said it was neither responsible nor involved in processing customs clearance for the shipments. All documents it received from Ikon Midstream, Torm added, consistently stated that the products carried on its vessels were "ULSD and/or naphtha." ULSD is the industry acronym for ultra-low sulfur diesel. Torm declined to share the documents it claimed to have received from Ikon Midstream with Reuters, citing contractual obligations.

"Based on what has come to light, we have decided to no longer do business with Ikon Midstream," Torm said in an email to Reuters on August 27, without elaborating.

Torm severed business relations with Ikon Midstream in early April and canceled two future contracts with the company, a Torm spokesperson said in a subsequent email to the news outlet on September 5.

As part of Reuters' efforts to seek comment from Ikon Midstream, a reporter visited the company's Houston headquarters in August but was turned away by a person who said he worked for Ikon Midstream and gave his name only as Daniel.

Kenagy, like many executives involved in the trillion-dollar global oil trade , projects an image of success. Earlier this year, he purchased a mansion and land in Houston valued at more than $6 million, according to local property records. His Instagram account is filled with images of sports cars, exotic motorcycles, and private jets.

He and his wife, Janelle Alexis Flatt, appeared in a 2022 episode of the reality show Below Deck Sailing Yacht, which chronicles the lives of crew members aboard a luxury vessel and their experiences with charter guests.

Flatt did not respond to requests for comment.

Kenagy is also the registered agent for at least half a dozen companies that are no longer operating, including mining, construction, and entertainment businesses, Texas business records show.

In Mexico, a Monterrey-based company called Intanza was the recipient of the Torm Agnes shipment, according to Mexican port records, as well as a shipping invoice from the company seen by the news agency.

Mexican authorities suspect Intanza is a front company for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, according to three Mexican security sources and a second undated government security document seen by Reuters that describes the cartel's ties to fuel smuggling.

Intanza has no website or social media presence that Reuters could identify. A letter sent by Reuters to the Monterrey address listed for Intanza on the invoice could not be delivered because the courier service could not find any company presence there.

The name Intanza resurfaced after Mexican authorities detained another vessel , the Challenge Procyon, on March 21 at the Port of Tampico in Tamaulipas state.

On March 27, Intanza filed a lawsuit in a Tamaulipas court asking a judge to release the shipment, which it claimed was lubricants and was unjustly seized; the judge denied Intanza's request.

Mexico's security secretary, Omar García Harfuch , said in a social media post on March 31 that 10 million liters (about 63,000 barrels) of diesel had been found aboard the Challenge Procyon.

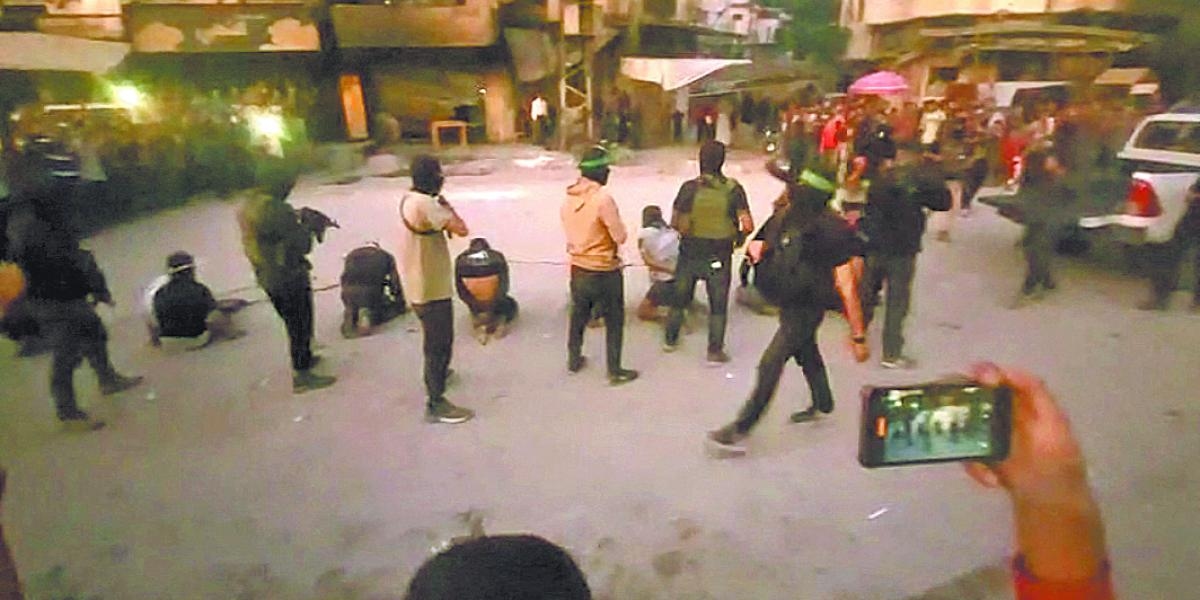

Last month, García Harfuch declared the seizure "one of the largest in history" when he announced the arrest of 14 people, including business executives, former customs officials, and active and retired naval officers, as part of investigations into Challenge Procyon and other alleged fuel smuggling. The government identified those arrested only by their first names, as is customary in Mexico.

The Navy and the Attorney General's Office said they could not comment on the ongoing investigations and referred public statements on the matter to Reuters. The Security Secretariat did not respond to a request for comment.

Ramiro Rocha, who is listed as Intanza's legal representative in Mexico's Public Registry of Commerce, said he has no relationship with the company and may have been a victim of identity theft.

A cartel sets sailFor decades, petty thieves known as huachicoleros have stolen gasoline, diesel, and crude oil from Pemex. Over time, as the business grew in scale and profitability, it attracted the involvement of Mexican cartels.

But the Jalisco New Generation Cartel has taken the plot to a new level and is the undisputed leader in fuel and crude oil smuggling, according to Mexican and U.S. law enforcement sources.

The cartel, whose home territory is the state of Jalisco in west-central Mexico, has expanded throughout Mexico. Authorities say it has established a formidable smuggling network in the northern state of Tamaulipas, just across the border from Texas.

From there, they say, it ships stolen Mexican crude oil to the United States and brings US refined products to Mexico by truck, train, and ship. They added that the CJNG is the only cartel currently using ships.

Authorities first detected vessel-based smuggling around 2020, according to a 2021 Mexican government document seen by Reuters outlining initial investigations into the scheme, which at the time did not attribute the development to a specific cartel.

The shift from trucks and trains to ships reflects a degree of business savvy and investment power that's in a different league than before, said Marisol Ochoa, an organized crime expert at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico.

"You have to have a high level of sophistication and a lot of networks and connections in logistics operations," he said.

Since September 2024, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has issued two sets of sanctions against a dozen Mexican citizens and nearly 30 Mexican companies allegedly linked to the CJNG and its fuel theft and smuggling operations.

Greg Gatjanis, a former senior OFAC official, said he was "stunned" by the variety of companies linked to the alleged scheme. These companies include gas stations, transportation companies, a 3D printing company, and a baguette bakery, according to OFAC.

In February, the Trump administration designated several Mexican cartels, including the CJNG, as foreign terrorist organizations. This mobilized more personnel and resources to combat the cartels and made it easier for U.S. prosecutors to pursue individuals and companies that do business with these groups.

In May, a Utah father and son, James Lael Jensen and Maxwell Sterling Jensen, were charged with conspiracy to launder money and providing material support to a designated foreign terrorist organization. Authorities allege the Jensens collaborated with CJNG to smuggle crude oil into the United States.

James Jensen's attorneys did not respond to a request for comment. Robert Guerra, Maxwell Jensen's attorney, declined.

U.S. officials also met with refiners in the Houston area this year to explain the involvement of Mexican organized crime in the fuel industry and emphasize the importance of knowing their suppliers and customers, three industry sources and a U.S. official said. The official told Reuters that those who violate U.S. sanctions in the supply chain could face civil and criminal penalties.

This represents "a huge commercial risk" for U.S. actors given the cartels' success in using front companies and intermediaries to do their dirty work, said Gatjanis, the former OFAC official.

In Mexico, the scale and increasing sophistication of fuel smuggling have led to accusations that high-level politicians are involved.

During last year's presidential campaign, opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez accused the ruling Morena party of receiving funds from Sergio Carmona , a Tamaulipas businessman known in the Mexican press as "the king of huachicol."

Carmona was a major drug trafficker linked to the Gulf Cartel and the Northeast Cartel, according to Mexican media. He was shot and killed in a barbershop in northern Mexico by unknown assailants in 2021. No one has been arrested for his murder.

Carmona allegedly helped finance Morena's election campaigns , including that of former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who won Mexico's top office in 2018, according to the second undated memo from government security forces reviewed by Reuters.

Neither López Obrador nor Morena responded to requests for comment.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, of the Morena party, has made combating fuel smuggling and crude oil theft a security priority for her administration.

"We're not going to protect anyone," Sheinbaum said at a press conference on July 8 when asked about the alleged involvement of politicians in illicit trafficking. Her office did not respond to a detailed list of questions for this article.

Since Sheinbaum took office in October 2024 , authorities claim to have seized around 500,000 barrels of allegedly illegal fuel and crude oil, more than the previous administration seized during its entire six-year term. This is just a small fraction of the torrent of illegal fuel entering the country. Still, the fight is proving dangerous.

On August 4, Tamaulipas prosecutor Ernesto Vázquez died after his armored vehicle was hit by an incendiary grenade on a busy Reynosa street. Images broadcast on national television showed Vázquez escaping the burning vehicle but being shot from a nearby car.

In a statement issued the following day, the Attorney General's Office said the killing was likely the work of organized crime , after the government seized more than 1.8 million liters (about 11,300 barrels) of illegal fuel, trucks, pumps and other equipment in late July in Reynosa, just across the border from McAllen, Texas.

A trail of tax evasionCrude oil and fuel trade often involves a complex chain of custody. Transactions can involve multiple buyers, sellers, and intermediaries. Import and export documentation is often incomplete or falsified by malicious actors, trade experts and law enforcement officials told Reuters.

Torm Agnes began loading from the Vancouver Wharves marine terminal in Canada on March 2, according to maritime data provider Kpler. The vessel loaded about 120,000 barrels, Kpler estimated, based on data transmitted by the tanker, which showed its depth. Seven sources familiar with the matter confirmed that it loaded diesel.

The diesel came from Imperial Oil, a Canadian oil company majority-owned by ExxonMobil, according to four of the people.

Imperial Oil did not respond to a request for comment. ExxonMobil declined.

Shipping documents reviewed by Reuters revealed a different version of the vessel's contents. A February 28 invoice, bearing the Ikon Midstream logo and a Houston address, stated the cargo consisted of lubricants, not diesel, and had been sold to Intanza. The declared value was $1.3 million, about one-tenth of the value of 120,000 barrels of diesel at the time. A cargo manifest reviewed by Reuters also showed the cargo consisted of lubricants loaded in Vancouver onto the Torm Agnes for delivery to Mexico, with Ikon Midstream as the shipper and Intanza as the consignee.

In recent years, Mexico has seen an increase in declared irregular imports of lubricants, a phenomenon the government has linked to smuggling. In a 2022 document, the country's tax authority stated that these products are used as a means of tax evasion because they are not subject to the IEPS (Tax Expenses).

Demand in Mexico for so-called petroleum-based lubricants is only 1 million tons annually, according to Michael Connolly, director of base oil refining and analysis at commodity information provider ICIS.

However, official U.S. trade data shows the country exported up to 3.5 million tons to Mexico last year, a figure Connolly says doesn't add up.

"There's a significantly higher level of imports coming in than we expected," he said.

Ikon Midstream alone reported shipments of lubricants from the United States to Mexico 149 times between October 11, 2019, and May 4, 2025, and 67 of those shipments arrived by ship, according to trade data compiled for Reuters by trade technology firm Altana.

Intanza, the Mexican client of the Torm Agnes cargo, has a range of business objectives, ranging from alcoholic beverage production to scientific research, according to Mexico's business registry.

Its Monterrey address, according to the shipping invoice, is a unit in a two-story residential complex next to a daycare center. When a Reuters reporter visited the address, she saw no sign for Intanza.

Rocha, Intanza's registered representative, lives in a working-class neighborhood about 40 kilometers from the city, according to his registered address.

The gray-haired Rocha became a minor online celebrity in recent years by posting videos of himself sleeping in strange places. A short, stocky man, his fans nicknamed him "Don Pug." His popularity resurfaced in February when he took to social media to deny press reports that he had died of a heart attack during an erotic dance at a Monterrey strip club.

Rocha told Reuters that he works as a security guard , has nothing to do with Intanza, and that the information about him in the registry, including his address and three forms of identification, may have been stolen.

A smooth operation, then a rushOn the afternoon of March 8, Torm Agnes entered the Port of Ensenada. Within hours, the line of trucks being loaded with fuel stretched from the dock to the outside, according to an eyewitness to the operation.

Some of these vehicles bore the logo of a trucking company called Mefra Fletes, according to the witness and a photograph of the scene seen by Reuters.

Ikon Midstream and Mefra Fletes have collaborated on ship-to-truck fuel transfers in at least three Mexican ports in recent years, according to two sources familiar with the operations. The employee at Ikon Midstream's headquarters in Houston in August, who identified himself as Daniel, told a Reuters reporter that he used to work with Mefra Fletes in Mexico.

Mefra Fletes was established in 2015 in Guadalajara , the capital of Jalisco state, and is dedicated to the transportation of petroleum products, according to the Public Registry of Commerce. The registry did not list an address or contact information for the company or for Roberto Blanco, who is listed as the majority shareholder. Reuters did not find a website or social media presence for Mefra Fletes.

Reuters did not receive a response to a letter sent by courier with detailed questions for Blanco to a Mefra Fletes address in Jalisco printed on one of its trucks. Journalists were unable to locate the company's legal representative, Mario Castro.

Torm Agnes unloaded much of its cargo in Ensenada. From there, it headed to the Port of Guaymas, on the Gulf of California , and again unloaded directly into tanker trucks starting on March 20, according to photographs and videos of the operation seen by Reuters. Some of those vehicles bore the insignia of Mefra Fletes, according to the images.

But Torm Agnes only managed to unload half of the planned cargo, according to internal port emails seen by Reuters. It departed Guaymas abruptly the next day, according to vessel tracking data and three people familiar with the situation. Workers helping to unload the diesel quickly packed up their equipment, and tankers sped out of the port, the sources said.

The exodus caused a stir locally. Photos and videos shared on social media showed a dozen fuel tanks detached from the trucks that transported them and abandoned in nearby parking lots and on the side of the road.

Security sources told Reuters they suspect Torm Agnes fled after word spread at the Port of Guaymas that Mexican authorities were seizing another vessel, the Challenge Procyon, that same day, March 21, at the Port of Tampico.

Torm did not comment on the reason for Torm Agnes's hasty departure. The Port of Guaymas did not respond to a request for comment.

On March 28, Mexican authorities announced in a press release the seizure of approximately 50,000 barrels of petroleum products haphazardly stored in about 100 containers on a dusty lot in the town of El Sauzal, about 10 kilometers north of the Port of Ensenada. Security forces also seized equipment and tanker trucks. Video footage of the operation, released by Mexican media, showed Mefra Fletes trucks.

The seized petroleum products likely originated from the Port of Ensenada and arrived on a ship, according to an undated summary of the case obtained by Mexican security forces and reviewed by Reuters. The document does not mention Torm Agnes, but two Mexican security sources confirmed that the tanker's activity in Ensenada is under investigation.

Anuar González, former legal representative of Mefra Fletes, was arrested in August. An arrest warrant was issued for Blanco, the company's majority shareholder. Both are suspected of involvement in illegal fuel trafficking , according to one of the Mexican security sources and press reports.

Reuters was unable to determine whether González has a lawyer. Blanco remains at large.

Eleconomista