Bullerengue, a genre of anonymous and resilient women

Teacher Petrona Martínez always dreamed of replicating the bullerengue wheel she witnessed as a child, where matrons over 60 years old, whom she now remembers as her ancestors, would gather to sing and dance to the sound of drums. That dream faded when she realized that she was possibly the last bearer of the bullerengue tradition.

Her greatest desire, which seemed impossible, was revealed to her producer, Manuel García-Orozco, a scholar and curious observer of Colombian folk music, who took on the dream as a challenge. Between 2015 and 2018, he set out to find women who preserved bullerengue in their homes and communities in the heart of the land of bullerengue: the Montes de María.

“Petrona didn't see any women her age (over 60) singing bullerengue around her, but I knew of one: Juana del Toro. She was a peasant woman who had never recorded. So I thought that if she was there, I'd surely find more,” said García-Orozco, better known as Chaco.

Through word of mouth, just as the bullerengue tradition has prevailed, Chaco traveled through the Montes de María, also known as the historical epicenter of the genre, and through the Dique canal to search for those anonymous women who carried on the legacy of their mothers and grandmothers, singing and resisting oblivion through music.

In addition to Juana del Toro, from María la Baja, Bolívar, other names appeared in that search: Juana Rosado and Carmen Pimentel, both from Evitar, also in Bolívar; Fernanda Peña, from San Cristóbal del Trozo, in the same department; and Mayo Hidalgo and Rosita Caraballo, also from María la Baja.

During those years, she met them, introduced them, brought them together, and recorded them during the bullerengue groups. And in 2019, thanks to all the material she had, she released the album Anónimas y Resilientes, voces del bullerengue, which earned a Grammy and Latin Grammy nomination. Petrona's dream came true with her presence and without her voice. During that process, in 2017, the maestro suffered a cerebral ischemia, which left her with hoarseness. "She was in the group we did for the first album, but she couldn't participate," Chaco commented.

Petrona Martínez with her gramophone. Photo: Twitter: @televallenato - Instagram: @mpetrona

Six years after their first album, the collective, together with Chaco, released their second album, #AnónimasyResilientes, in which they remember those who are no longer with us, such as Fernanda Peña, who died in 2021 at the age of 106, becoming the oldest member of the group, and in which they bring together new voices who, in their territories, keep bullerengue alive, such as Yadira Gómez de Simanca, nicknamed the 'Chamaría de los Manglares', a woman who has traveled back and forth between Pontezuela, Tierra Baja and La Boquilla, a fishing village on the outskirts of Cartagena.

A gender of women According to Chaco, bullerengue is a genre of Afro-Colombian culture. “Although it's a genre closely associated with the history of slavery, I prefer to view it more from the perspective of the maroonage, because it was through freedom and resistance that we were able to preserve what was completely forbidden . My theory is that the free people of the Montes de María were able to preserve the matriarchal lineages of Africa, and that's why bullerengue is a predominantly female genre,” explained Chaco, who holds a PhD in Ethnomusicology.

In the article "From Marginalized Music to Cultural Export ," Chaco discusses other theories from academics that explain the reasons behind the matriarchal tradition. Some say that bullerengue is a genre that originated among pregnant, unhusbanded women who did not participate in official celebrations; others say that women were not allowed to make music in the presence of men; and still others have suggested that the genre originated as a ritual for motherhood, a West African heritage, and that it later acquired a festive character.

Whether these theories are true or not, bullerengue managed to spread to territories other than the Montes de María across the Magdalena River, reaching other Afro-Colombian populations in Urabá, even in Panama. Its penetration was more local than national, as the genre began to be discussed in the country some 40 years ago thanks to the figure of Petrona Martínez.

Bullerengue, then, was an invisible form of music, and that has led to its history being unclear and obscure. Experts agree that it was a genre that had little influence from the Spanish, which is why it is one of the few folklore genres that does not incorporate the guitar.

Bullerengue is also characterized by its cyclical, spiral music. That is, there is freedom to vary and improvise . “A song can last three minutes one day and seven the next. This genre is open to the spontaneity of the moment. The role of the drummer, who dialogues with the singer, plays a significant role in this. And repetition is part of the language,” Chaco explained.

A song can last three minutes one day and seven the next. This genre is open to the spontaneity of the moment. The drummer plays a significant role in this, as he dialogues with the singer. And repetition is part of the language.

Although bullerengue is a predominantly female genre, it does feature male drummers. The reality is that there are few female drummers, and one of them is the "Chamaría." The Anónimas y Resilientes project includes men on drums and in backing vocals. Even the first album featured songs by Antonio Verdeza and Jaiber Pérez Cassiani, the latter a rare exception. "Jaiver is young and I thought he was very talented. He came from backing vocals and ended up recording a couple of songs on the first album. And Antonio Verdeza caught my attention because he told me he learned bullerengue from his two grandmothers. He was over 90 years old and has since passed away," Chaco noted.

Generational transfer All the singers who are part of the project, like Verdeza, mention their grandmothers, mothers, aunts and cousins as those responsible for transmitting the bullerengue tradition , a purely oral tradition, different from what happens in other Afro communities that have musical festivals that allow them to preserve their culture.

For example, 'Chamaría' mentions a distant cousin of her father's as the woman who inspired her bullerengue as a child. She always loved music, but it wasn't until she was 40 that she began to explore her singing career. "One day I was on my father's small farm and I saw some clouds gathering. I grabbed a small drum, started playing it, and sang 'A big cloud is approaching / It looks like it's going to rain / If it doesn't rain now at night, / Suddenly at dawn,'" said 'Chamaría,' a nickname for a Caribbean bird that sings loudly and repeatedly, like her.

Yadira Gómez, nicknamed the Chamaria of the Mangroves. Photo: Andrea Moreno. El Tiempo

This is how "Se acerca un nubarrón" (A Cloud Approaches) was born, a song that inspired her to build her musical career outside of her job as a fisherman. Her name is now part of the history of bullerengue. In 2012, she sang for Barack Obama and Shakira during a ceremony to hand over collective lands to Afro-Colombian communities . To this end, she composed "La titulación" (The Title), which is part of Anónimas y Resilientes' second album. "I'm not leaving / I'm staying here / I'm not leaving / I'm staying here / this land is mine / I'm staying here / to raise chickens / pigs and sheep," is heard in the chorus.

Chamaría's voice is deep, powerful, and husky. "Building a voice like hers takes years. A 10-year-old girl can't sing like her, but when she grows up, she'll surely want to emulate that acoustic power. Many of the singers start out imitating their grandmothers," Chaco explained.

Building a voice like Chamaria's takes years. A 10-year-old girl can't sing like her, but when she grows up, she'll surely want to emulate that acoustic power. Many singers begin by imitating their grandmothers.

That's why Anonymous and Resilient is a project of women over 60 years old that gives space to those who, for years, have built a voice that is and will be the legacy for their daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters, who in the future will imitate the purity of the bullerengue tradition, summoning a circle like their ancestors.

The "Chamaría" is a fixture in Villa Gloria, near La Boquilla, where she currently lives. One of her daughters, granddaughters, and neighbors accompany her with clapping, dancing, and singing along when she suddenly bursts into song. They, for example, are the ones destined to continue her legacy when they grow older .

Anonymous and Resilient is a collective project designed not only to give recognition to the country and the world for these older women who secretly created traditional music for so many years, but also so that generations of daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters of the 'Chamaría' and the other members can hear their voices without having to imagine them.

The project is also considering a virtual reality video, which will be the next step for Anónimas y Resilientes. "We're thinking about the future, so that future generations can see this material and be grateful for those ancestors who protected the family, its traditions, and values," Chaco added.

Unlike the albums of Maestro Petrona, in which he intervened as a producer, making arrangements and thinking about how to blend bullerengue with mariachi, for example, Chaco's role in Anónimas y Resilientes is to amplify what the singers have done for years and continue to do because it is something very much theirs, it is their essence, it is their culture.

“The recordings for this second album were done in the countryside. I put the microphone in the middle of the circle, with an augmented reality camera, and that's it. Everyone can clap or shout whenever they want. That's part of the social dynamic of the genre, and we preserved it in the phonogram,” Chaco explained. Although there is work behind the scenes after the recordings, the sound ultimately sounds very real and organic. And the video doesn't have any cuts or montages.

Today, there are schools like Tambores de Cabildo in La Boquilla that preserve this tradition, but, in Chaco's opinion, the best school will always be the homes of these matrons who manage to bring their entire community together through song and love. "That is a very beautiful exercise of power," said the producer.

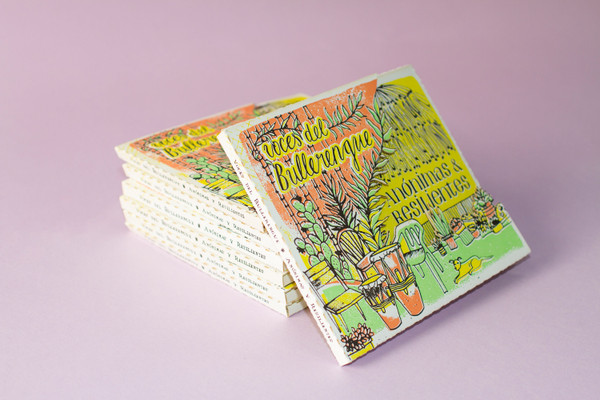

Anonymous & Resilient Album Photo: Anonymous & Resilient

Teacher Petrona and Anónimas y Resilientes expand the country's identity with bullerengue; however, as rural and Afro-descendant women, they face structural barriers, such as illiteracy, poverty, and a lack of geographic and internet connectivity , which would have prevented them from becoming more well-known, to name a few factors that have rendered their tradition and art invisible.

This second album not only continues to fulfill maestro Petrona's dream, but also continues to democratize a very Colombian genre that celebrates the diversity of the country's Afro-Colombian communities and was recently declared an intangible cultural heritage of the nation. "It makes me very happy that so many people know me and what I do, because singing is my thing," concluded 'Chamaría'.

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F26e%2F7bd%2Fd37%2F26e7bdd37269e6439b3d1760e8ca5901.jpg&w=3840&q=100)