Astronomers capture an image of a potential planet forming around star

Astronomers believe they have caught a planet in the act of forming, something that has never before been witnessed.

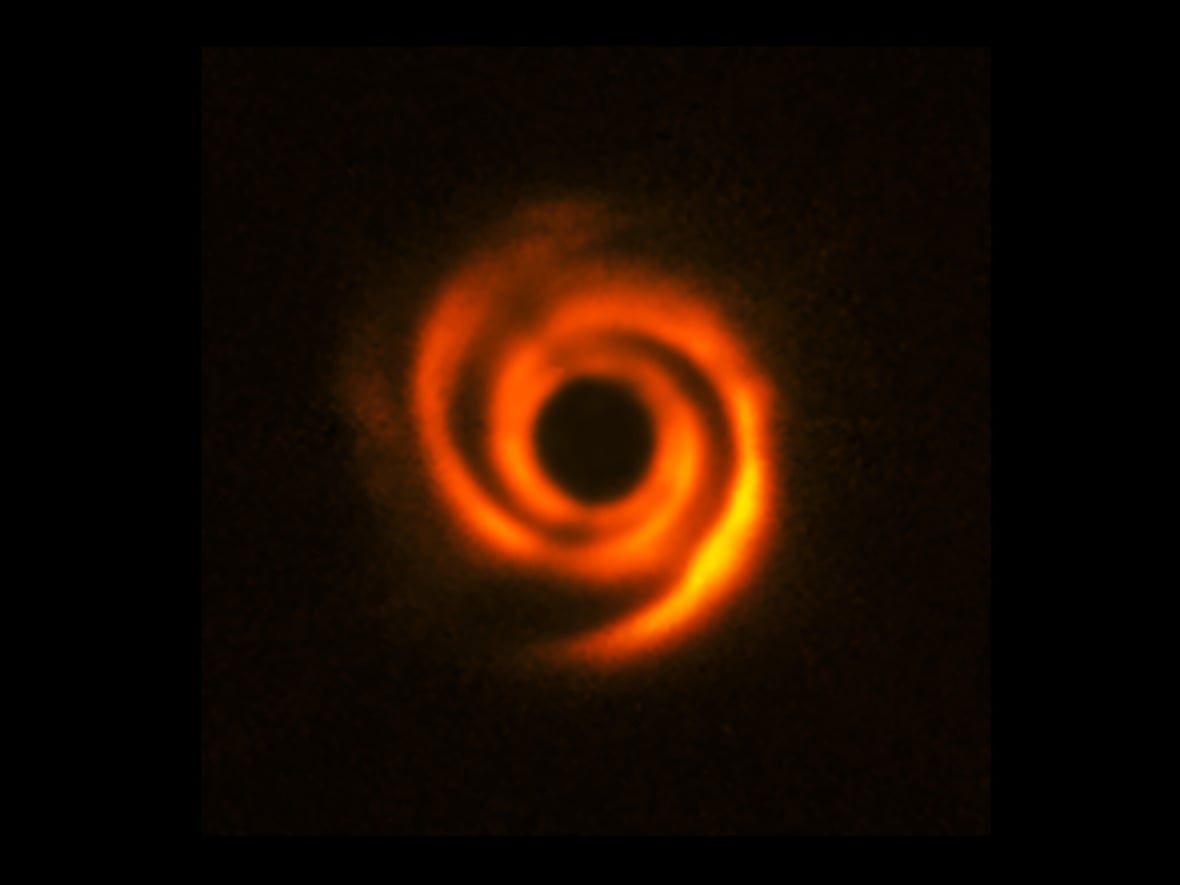

Planets form out of the leftover gas and dust once a star has ignited, and it's believed that the forming planet or planets create a disk around the host star. While astronomers have seen this protoplanetary disk around many stars, they have never before photographed an actual planet forming within, an action that creates spiral-like structures.

While earlier observations of this star didn't reveal any object that could be orbiting it, the team that made this discovery used a different instrument that looked at it in a different wavelength.

The authors of the study, published Monday in the journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters, say they haven't yet confirmed that what they've captured is the formation of a planet or protoplanet.

"We have only one image [in] only one wavelength," said Francesco Maio, a doctoral researcher at the University of Florence, and lead author of the study. "We have three images where we don't see this object. So we need to understand the properties of these candidate protoplanets."

The object is roughly 440 light years away in a binary, or double, star system, and is believed to be twice the size of Jupiter. It orbits its host star at a distance similar to that of Neptune's distance from the sun.

'Like a cappuccino'Maio described finding the potential planet in the disk in a uniquely Italian way.

"The disk is like a cappuccino. The planet is like a spoon in the cappuccino. And when you move the spoon inside the cappuccino, you start to form spirals," he said.

Though scientists have previously observed the spirals, Maio says this is the first time they've been able to see what is potentially causing them.

"We are not able until now to see the planet that perturbed and generated a spiral," he said. "So you already see this cappuccino with spirals, but we never see the spoons."

The discovery was made using the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and its Enhanced Resolution Imager and Spectrograph (ERIS) instrument at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile.

The disk itself was imaged by another team of astronomers using a different instrument called SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch), which can block out the light of a star in order to see if there are any objects around it. But the previous researchers didn't find anything orbiting the star.

Still, researchers say it's promising.

"This is an interesting observation. People have been seeing these spiral structures in protoplanetary disks for a long time," said Hanno Rein, an associate professor at the University of Toronto and an exoplanet researcher who was not part of the study.

"What's usually missing is the object that is actually creating those spiral arms, or that is forming in those disks. And this team here seems to have found one strong candidate of an object that is at the base of one of those spiral arms that might be a planet forming."

2 stars, different environmentsAnother interesting twist to this discovery is that there is another star in the system, whose environment is very different.

The pair are collectively known as HD 135344AB. The star that this potential planet is orbiting is HD 135344B.

Both stars are roughly the same age, Maio said. Yet, the other star in the system — HD 135344A — has no protoplanetary disk.

"This is very interesting, scientifically speaking, because we don't know why two very similar stars evolved together as two different systems," Maio said.

Earlier this month, astronomers looked at the second star with ESO's VLT and SPHERE instrument and found a planet with roughly 10 times Jupiter's mass.

While that's one mystery, the question of whether or not there is a protoplanet in the disk of gas and dust from Monday's study will need further investigating, Maio said, and will likely require using other wavelengths to look.

cbc.ca