NIL Goes to High School: Million-Dollar Teen Quarterbacks, Legal Battles, and Fast Cash

Thank God Julian Lewis played his high school football in Georgia. Otherwise, dear Coco might not still be with us. Back in the spring, Coco, the seventeen-year-old star quarterback’s beloved miniature dachshund, got sick—like three-days-in-the-ICU, emergency-surgery, wipe-out-your-savings kind of sick. But because the Peach State lets high school athletes make money off endorsements, Lewis could afford the $11,000 vet bill. He was also able to buy himself a Tesla Cybertruck (starting price $79,900). And a Dodge Ram TRX (starting price $98,335). And a Lamborghini Urus (starting price $241,843). And, just for fun, a Darth Vader chain encrusted with black diamonds, too (price undisclosed).

Would he have been able to pay for these things without endorsement deals as a high school athlete? I ask a shirtless Lewis over FaceTime in June. He’s just returned home from a workout at the University of Colorado. The quarterback from Carrollton, Georgia, whose nickname is “JuJu,” was ranked No. 2 on the 2025 ESPN 300 list of the top recruits in the country. This fall he’s competing to be the starter as a true freshman on Coach Deion Sanders’s buzzy team.

“No. Impossible,” he tells me before he’s interrupted by a loud series of woofs coming from upstairs. It’s his new dog, an enormous gray-blue cane corso named Smoke with a loud bark. “I mean, we weren’t poor, but we weren’t financially on the hierarchy of the earth. Definitely no big black chains.” Safe to say no Lamborghinis, either.

Lewis is part of a new era in high school sports—one that began, somewhat unintentionally, in 2021, when the NCAA reversed its century-old amateur policy and started allowing college athletes to profit from their so-called name, image, and likeness (or NIL, for short). That decision didn’t apply to high school athletes, but it didn’t have to. The moment college athletes were cleared to cash in, high school rules about athletes and money became outdated overnight. Most had been written to protect students’ NCAA eligibility, which used to hinge on maintaining amateur status—no contracts, no payments, no perks. But with that standard erased at the college level, the logic behind those high school restrictions fell apart.

The rules would have to change, and soon enough they started to. The problem is, though, they haven’t changed everywhere all at once. So while Lewis was free to sign endorsement deals that allowed him to graduate high school with three cars, had he grown up twenty miles west in Alabama, where NIL is still banned in high school, who knows what his garage would’ve looked like—to say nothing of little Coco’s fate.

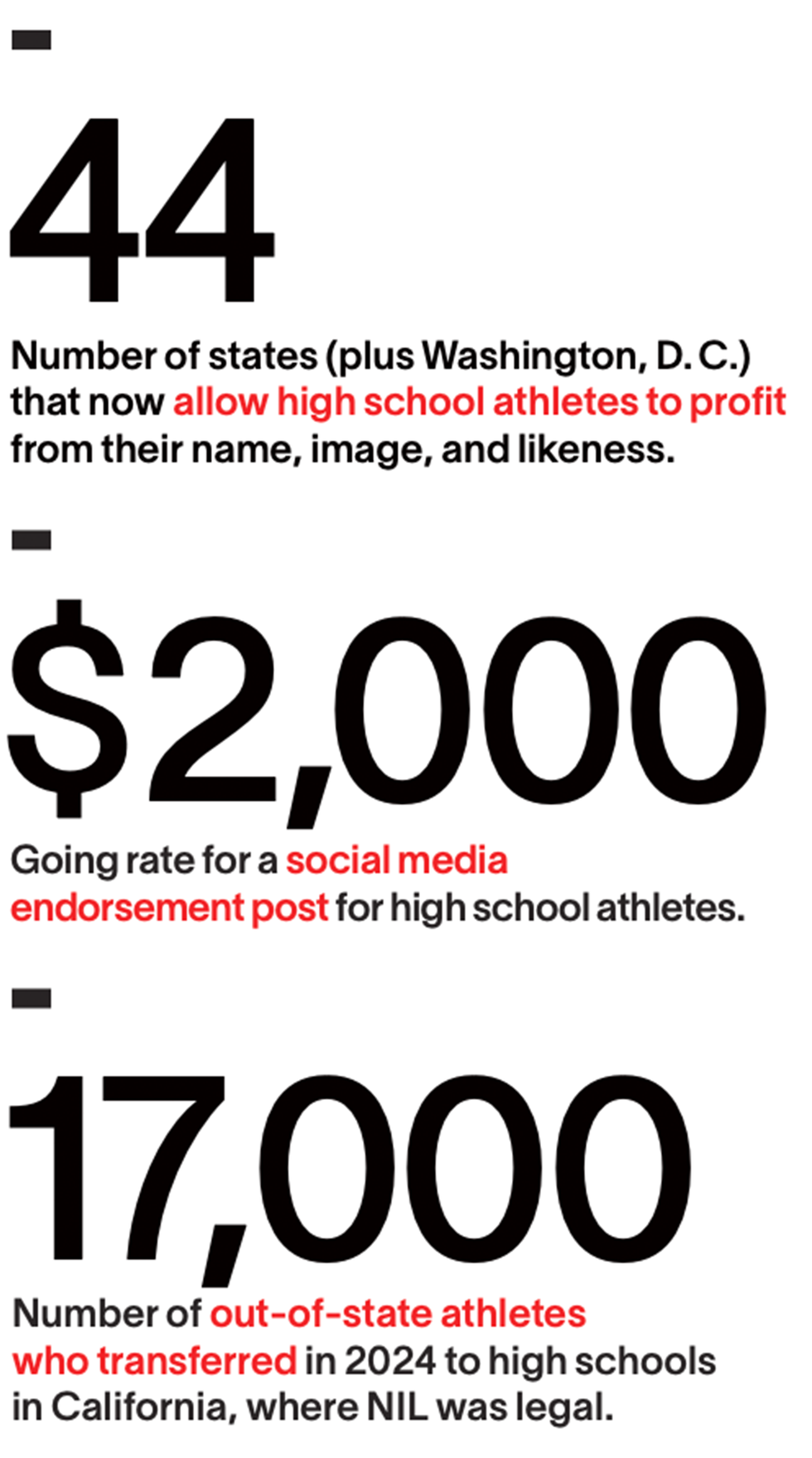

As of this summer, forty-four states plus Washington, D. C., now allow high school athletes to profit from their name, image, and likeness. Only a handful—including Alabama and Ohio, known for powerhouse college football programs—still do not. But even among those that do, no two states regulate NIL quite the same way. Some states, like Louisiana and California, are more lenient. Others, like Virginia, are stricter. In Missouri, student athletes are allowed to begin profiting from endorsement deals while still in high school only if they have signed a letter of intent to attend an in-state public university. In Texas, they have to be at least seventeen before they sign an NIL deal, and they can’t profit from it until they have graduated. And until recently, in North Carolina, NIL was permitted in private schools but banned in public schools.

The result is a messy state-by-state patchwork of rules that has created a nation of unequal opportunities for today’s top athletes, leaving some blue-chip quarterbacks like Lewis incredibly wealthy at a young age; others, like top quarterback recruit Trent Seaborn from Alabama, forced to either move or turn down major financial opportunities; and coaches and families scrambling to figure out how to navigate a newly monetized landscape that some experts say has the potential to undermine the entire academic enterprise as we know it.

Whether the most dire predictions come true, one thing is already clear: For elite high school athletes, the days of playing purely for the love of the game, for the bright Friday-night lights that shine over your local school district, are over.

Top: Julian Lewis with his Lamborghini Urus outside of Boulder, Colorado. Above: Lewis dining with his father, T.C., who manages his son’s NIL opportunities, letting Lewis keep his focus on football.

Lewis is yet to take a snap in a college football game. But his NIL valuation as a high school senior was estimated to be $1 million by On3, a site that covers high school and college recruiting. (Now that he’s in college, it’s even higher.) To be clear, Lewis is an outlier. Most high school athletes will never make anywhere near that amount. For the average player, the NIL market is nothing like it is in college, where six-figure deals abound. According to Braly Keller, director of collegiate services and insights at the sports-marketing firm Opendorse, commercial high school NIL deals can range anywhere from $500 to $2,000 per social-media post endorsing a brand or business, depending on the player’s follower count and the town they live in.

“The vast majority of high school players are locally famous,” explains Stanford economist and leading NIL expert Roger Noll. “No one’s ever heard of them except people in their hometown. But their image is valuable to, say, the local hamburger shop.”

Or, in Lewis’s case, the local car wash. One Way Detail, in Carrollton, washed his Dodge Ram TRX for free in exchange for a social-media shout-out. There was also a local restaurant that let him and his buddies eat on the house if they brought other people in. “We threw his sixteenth birthday there,” says Lewis’s dad, T.C. He’s on the FaceTime call too, and he’s also annoyed by Smoke’s intermittent barking.

But even for a five-star recruit like Lewis, the opportunities within the state of Georgia were limited. “Businesses didn’t understand it,” says T. C. At least they didn’t two years ago.

Things are changing fast. Doug Young, the chief marketing officer for QB Reps, a sports-marketing agency that represents top quarterbacks starting in high school, has noticed the high school NIL market picking up in the past year, at both the state and, especially, the national levels. “There are more brands that are now familiar with the value of high school NIL and are actually allocating resources in this space,” says Young.

"These kids, the ones that aren't getting any money, are probably wondering, 'Where my money at?' It kind of creates a really big cancer."

At the same time, they are exclusively interested in athletes who can deliver an audience—an increasingly large part of the job for the most business-savvy players and their parents. “I have Instagram, I have a YouTube channel, I have Twitter. I have every social media possible now,” says Lewis, whose loosely coiled honey-blond curls spill out from a black toboggan with the word alo on it. “So I think brands understand they’ll be seen.”

In fact, Lewis is showing off a brand as we talk. The high-end activewear label Alo cut its first and only high school NIL deal with Lewis back in February 2024. T. C., who is also wearing an Alo hat, won’t discuss the details—“We never disclose how much we make,” he says politely but firmly—but it wasn’t Julian’s biggest deal. Nor was the Under Amour “Back to School” campaign that he did last summer. Or the deal he did with the rapper Travis Scott’s clothing label, Cactus Jack. Or the endorsement with Jaxxon, a high-end men’s jewelry company.

No, by far the biggest deal Lewis did was with Leaf Trading Cards, a small-but-mighty Texas-based card-manufacturing and collectibles company that inks autograph deals with celebrities in the pop-culture and sports worlds. (That includes Haliey Welch, aka the “Hawk Tuah” girl, who went viral for her explicit description of how to give a good blowjob. Her thousand-card run sold out in less than a day last year.) Leaf doesn’t have the rights to produce officially licensed cards from leagues like the NFL or the NBA, but it does have a bold, creative business plan.

Now, if you’re wondering how much a trading-card company could possibly pay a seventeen-year-old athlete for their signature on some shiny cards, the answer is a stupid amount. In Lewis’s case, according to the agent who brokered the deal, Leaf paid him “a significant six-figure deal at first-round NFL quarterback values.” Not bad for a few thousand signatures. And Lewis was just one of many high school athletes whose wallets Leaf has fattened recently. “In terms of overall dollars spent on NIL in high school, we’re probably the number-one company in the world,” says Leaf’s president, Josh Pankow. “We’ve done millions and millions of dollars in that space.”

In March, Leaf struck a deal with Jared Curtis of Nashville, the top quarterback recruit in the class of 2026, who’s committed to play for the University of Georgia. Curtis posted a video of his new neon-red Corvette a few months after the deal was announced. The company also snagged Faizon Brandon of Greensboro, North Carolina, another top recruit in the class of 2026, who evidently “sells pretty well for being a high school quarterback,” says Pankow.

Which is nice. However, it actually doesn’t matter too much to Leaf if a high school player’s cards sell well on their own. The company mixes them into themed variety boxes of cards that collectors buy in hopes of snaring a few gems. And Pankow says that Leaf makes a margin on these sales. But that’s not where the real profit potential lies.

Pankow is thinking longer-term. Forming relationships with the athletes now gives the company a chance to capitalize on additional memorabilia later on with players who make it big in college and pro sports. “The idea is that once they become stars, people will go back and buy their cards,” says Pankow. If Lewis and Brandon become the next Brady and Mahomes, Leaf’s investment should pay off hugely.

As for the families, it’s a no-brainer because, according to Pankow, no other trading-card companies are going after fifteen-year-old athletes like Leaf is. They might approach players after they graduate and sign with a top program like Texas, but Leaf is willing to give them two years of cash before that. Cash that can be used to offset the exorbitant cost of playing high school sports at an elite level—or purchase a Corvette.

Despite what seems like an easy way to make huge sums of money, there are still some top athletes who don’t—or can’t—take the deal.

That was originally the case for Faizon Brandon before his family took action. Last summer, they sued the North Carolina Board of Education for its ban on NIL in public schools. The rule had been put into place shortly after the North Carolina Independent Schools Athletic Association, which governs the state’s private schools, decided to permit athletes to accept NIL money. “That set us up for a showdown between public schools and private schools,” says Brandon’s lawyer, Mike Ingersoll, who then brings up Brandon’s fellow top recruit, David Sanders Jr., to illustrate his point. Evidently Sanders, who attended a private school in Charlotte, already had a personal website where he hawked T-shirts with his face on them for forty dollars a pop by the time Brandon filed his lawsuit. “It was almost a perfect one-for-one comparison,” Ingersoll says about the two recruits, “which really set up the absurdity of the ban.”

Among the many points Ingersoll argued were that NIL gave private schools a competitive advantage and that North Carolina’s policy could cause players to leave the state.

It certainly would’ve caused the Brandons to leave. They were prepared to relocate to Tennessee for Faizon’s senior year if the judge ruled against them. And had they done so, they’d hardly be the only ones. Tales of students ditching schools and states for lucrative opportunities elsewhere abound in the high school NIL world.

Of course, top high school athletes have always moved around, but usually it was for competition or a chance to play on a better team, not cash. Now, says the quarterback agent Young, “families are moving across state lines to switch schools or to access opportunities—real or perceived—that may not exist in their home state.”

In fact, so many high schoolers transferred from other states to California schools in 2024—some seventeen thousand athletes—it rang alarm bells at the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), prompting the organization to begin closely monitoring potential NIL-motivated transfers. In that case, they may want to keep an eye on Alabama.

Trent Seaborn, the star quarterback for Alabama’s Thompson High Warriors, turned down a $1.2 million trading-card deal because the state doesn’t allow high school NIL payments and he didn’t want to abandon his team.

It used to be that athletes moved to Alabama from surrounding states like Georgia, Tennessee, and Florida for the chance to play at one of the state’s several powerhouse schools. “We have Central Phenix City, that’s a 7A school. We have Smiths Station, that’s a 7A school. We have Opelika, 7A school,” says Alabama state representative Jeremy Gray, naming high schools that play in the state’s most competitive division. He keeps going. “Auburn high school, that’s a 7A school. All within a thirty-mile radius.”

But now, says Gray, it’s the other way around. Case in point: Phenix City, a border town in Gray’s district that’s separated from Columbus, Georgia, only by a short, narrow bridge over the Chattahoochee river. According to Gray, there’ve been a lot of Columbus high schools “poking at athletes” to cross the bridge and play for them ever since Georgia legalized NIL. It’s happening in other border cities, too. Huntsville. Orange Beach. According to Gray, who recently introduced legislation to legalize high school NIL deals in Alabama, his state is losing star athletes left and right because of NIL. “Alabama student athletes are really missing out on these opportunities,” he says.

One such athlete is Trent Seaborn, a star quarterback for the reigning Alabama state champions in 7A, the Thompson High Warriors, and a top recruit in the class of 2027. Seaborn was relaxing in his living room in Alabaster, Alabama, one night last summer when his dad, Jason, approached him and told him he had good news and bad news. The good news was that Leaf Trading Card company wanted to pay him $1.2 million, spread out over multiple payments across four years, for a run of autographed cards. “I was honestly blown away,” Seaborn tells me, his deep, baritone voice sounding slightly out of sync with his baby face that is yet to need a razor.

The bad news was that if he wanted to take the deal, his family would have to leave Alabama. The Seaborns had already moved once for Trent’s football career, from Colorado to Alabama, so he could play for one of the best high school programs in the country. He wasn’t about to make them do it again, especially since it would mean having to leave his coach and teammates, who had done so much for him. “It would just be so disrespectful,” Seaborn says. “I just couldn’t do it.”

It probably helped that Seaborn didn’t want for much, either. He’s not the kind of person to spend money on himself. “I wear the same clothes every day. I drive my grandpa’s truck, so [the money] isn’t really a big deal to me,” he says.

HIGH SCHOOL NIL BY THE NUMBERS

His dad was relieved. “We truly feel like God led us to Alabaster,” says Jason. He was proud of his son for not being swayed by a “big pile of money.” Prouder than he’d ever been of anything Trent had done on the football team before—“no question.” Jason believed turning their backs on the good people of Alabaster, not to mention God, for money would be “distasteful.” But shortly after their decision, the Seaborns encountered a few financial hardships. “I don’t know if this was God testing us or what,” says Jason, “but I was like, ‘Boy, a little bit of financial help could sure help right now.’ ”

That’s when Jason’s opinion on NIL and money began to evolve. “It’s easy to be on a moral high horse when you’re not being pressured,” he says.

So while the Seaborns remain dead set on not moving states for NIL opportunities, they have warmed to the idea of it being permitted in Alabama. Jason even provided a carefully written statement in support of Representative Gray’s bill, calling on lawmakers to simultaneously “protect the life-shaping experiences of high school athletics and defend our young athletes’ right to work and earn wages in a legitimate and bona-fide manner.”

Seaborn himself is measured when he describes his opinion on NIL, answering the question like it’s an SAT essay prompt. “There are a lot of perspectives on NIL in high school,” he says. “There are many pros and cons.” On the pro side, it provides income, “and money is always good for everybody,” especially kids who come from financially strapped circumstances. But money changes people, too, and Seaborn worries that NIL could create problems in the locker room. “These kids, the ones that aren’t getting any money, are probably wondering, Where my money at? It kind of creates a really big cancer,” he says.

Above all, the Seaborns want lawmakers to ensure that NIL isn’t used as a “fig leaf,” as Jason wrote in his letter, for pay-to-play schemes. It’s a concern he shares with basically anyone who has watched NIL radically transform the college sports market into a billionaire’s spending spree for the best athletes money can buy over the past few years.

When the NCAA changed its rules to permit athletes to profit from endorsements, the intention was not for athletes to receive direct payment for playing from the schools they represented on the field or the court. Technically, schools were still forbidden from making “pay-to-play” deals with athletes. But this is America, land of opportunity, where every new set of rules quickly invites its own loopholes.

And that is exactly what’s happened in college sports: Instead of universities directly paying athletes, groups of university-affiliated donors formed so-called collectives to funnel money to top recruits, packaging direct cash payments as NIL deals in exchange for their commitment. The collective system is a “pay-to-play scheme disguised as NIL,” said Tony Petitti, commissioner of the Big Ten Conference, at a Senate hearing in 2023.

Recently, a pair of major developments shook up the world of college NIL. First, in June, a federal judge approved a joint settlement of three separate lawsuits that paved the way for colleges to begin paying athletes directly. Then, in July, President Trump issued an executive order called “Saving College Sports” with the intention of reining in “an out-of-control, rudderless system” of boosters pooling money to buy the best players for their schools. It’s unclear if the order will be interpreted as a legally binding blueprint or how it would be enforced, but it could signal future changes that would limit the spending power of collectives.

That would come as a huge relief to many high school NIL lawmakers and athletic-association directors who have looked on in horror at the money-powered free-for-all that college sports has become over the past few years. “Collectives are disturbing,” Karissa Niehoff, executive director of the NFHS, told a policy journal this year. The organization did not want what happened at the college level to occur in high school. As a result, many of the policies that now exist on the state level include specific bans on recruiting inducements and collectives.

And yet every day, rumors swirl about certain kids getting phone calls with offers. “We never got that call,” says T. C. Lewis. “I hear about those calls, but I never got it.” Jason and Trent Seaborn haven’t gotten that call, either. But they know people who have, including Trent’s teammate Cam Pritchett.

Earlier this year, word got out that a Tennessee high school collective offered Pritchett $750,000 to transfer schools. The star defensive end turned it down, but the news rippled through amateur-sports circles. X users tagged sports reporters in the post’s comments section and urged them to look into it. The Associated Press even picked it up.

Cam’s parents declined to comment on the offer, saying only that the collective’s representative warned them the school could face consequences if anyone discovered their involvement. Indeed it could. Assuming the school was a member of the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association, which the vast majority of high schools in Tennessee are, the offer would be a violation of TSSAA’s recruiting rules and explicit ban on collectives. Consequences could include fines and even a season-long suspension. The executive director of the TSSAA did not respond to multiple requests seeking comment on the incident.

High school sports fans on X may have been dismayed by the supposed pay-to-play offer, but the reality is that similar ones are doled out every single day, according to nearly everyone I spoke to for this article. And in some respects, they always have been.

Representative Gray says he saw his fair share of hundred-dollar handshakes when he played high school football in the early aughts. But the bagman of yesterday, with his cash-stuffed envelope, doesn’t compare to the post-NIL collectives of today with their six-figure phone calls in terms of potential to upend fair play. And it seems the high school athletic associations have little power to stop it.

Faizon Brandon, a top quarterback recruit from North Carolina, signs cards next to Leaf Trading Cards president Josh Pankow.

The funny thing about high school NIL is that, for all the fear and anxiety it creates, most people support it. As Noll, the Stanford NIL expert, points out, “This isn’t politically unpopular.” State laws and rules have changed so fast because the general consensus is that young athletes should be able to profit off their talent, especially considering how much money they generate for their schools via ticket sales, merchandise, and broadcasters’ increasing investment in high school sports. The idea of cutting kids in on all that cash just seems like the fair thing to do.

But the implications of actually doing it? The unintended consequences? What a fully commercialized high school NIL market might look like in five or ten years? That’s where the fear sets in. And everybody is worried about something.

Donovan Dooley is concerned about the impact on the psyche of young athletes. An independent quarterback coach for several of the nation’s top QBs, Dooley worked with the class of 2025’s number-one recruit, Bryce Underwood. In the past few years, he’s had a close-up view of how NIL alters a player’s life. “You lose a little bit of your childhood,” Coach Dooley says, “because it’s really work.”

That is very much true. All those photo shoots, social-media posts, and autographs? They take effort and time to produce, and teens don’t always understand what is expected of them when the money first comes in. So Dooley helps them wise up and get to work, starting with kids as young as eight years old whose parents are already thinking about how they can capture NIL when their kids turn fourteen. As a result, Dooley has had to expand his coaching services to include financial-literacy and business skills both for the players and, more importantly, for their parents, because ultimately they are in charge of the talent.

And what about the parents? What are they most worried about? Primarily bad actors. As well they should be. As with any nascent, underregulated market, there are plenty of sketchy operators looking to take advantage of the chaos and get rich quick—in this case, off athletes who may not know any better. Just ask T. A. Cunningham, who left Georgia for NIL-friendly California back in 2022 before his home state had changed the rules to allow NIL. Agents promised to deliver a slew of deals once he arrived. Instead, Cunningham found himself locked into an exploitative contract, failed to get a single endorsement, and was benched early in the season after the California Interscholastic Federation decided he’d broken transfer rules. His status as a top recruit dropped immediately and he recently transferred to a junior college after failing to make an impact at Penn State.

But for once, the most concerned group of all is not the parents. It’s the educators and the experts. The people who are really thinking long-term about this and considering worst-case scenarios? They’re freaking out.

Roger Noll is remarkably cheery sounding for a man who just told me he is concerned about the complete destruction of the academic enterprise on account of the commercialization of high school sports. And Noll is pro-NIL! He views it as a rare opportunity for the vast majority of high school athletes—who’ll never reach college sports, much less the pros—to profit from their skills while they still can.

What he’s worried about, though, is that if high school NIL isn’t channeled properly, if those in charge fail to come up with the right guardrails, it will make athletic powerhouses even more powerful. Case in point is California’s Mater Dei, a Catholic prep school in Santa Ana with one of the top high school sports programs in the nation. Mater Dei recently inked a deal with a company called Playfly Sports that made it the first high school in the country with a seven-figure multimedia-rights agreement for the express purpose of enhancing the school’s “sponsorship opportunities, media exposure, and fan engagement.” So Noll is probably right to feel like, in this case, the rich may be getting richer.

Mater Dei provided a statement to Esquire in response to questions about its deal with Playfly that reads, in part: “Mater Dei High School does not negotiate or facilitate NIL deals for student-athletes. Our partnership with Playfly Sports is focused solely on institutional sponsorships that support school-wide programs—not individual endorsements. . . . We remain focused on our mission to form young men and women with Honor, Glory, and Love—on and off the field.”

According to Noll, as more money flows into their athletic departments, wealthy schools could become professionalized sports franchises that pay lip service to education. “Do you really want kids at about age fourteen or fifteen to become de facto professional athletes instead of students?” he asks.

Also, how can schools with fewer resources be expected to keep up? And if they can’t remain competitive, what will that do to school spirit, to the community, to the school’s resources? As Noll reminds me, “the political support for the budget of the school district is positively affected by the quality of its high school sports team, sadly.”

These are big questions in need of big answers that are yet to arrive.

But Julian Lewis isn’t grappling with those issues. His job is to focus on football. “To keep the main thing the main thing,” as T. C. likes to say. Because the NIL income won’t keep gushing if he doesn’t play well at the college level. And T. C.’s job is to look out for his son and handle his business, which he and his team appear to excel at. They’ve got plenty of money stashed away for Lewis later, a whole host of financial advisors to protect him from himself (now that he has plenty of vehicles), and an extremely diversified portfolio. The kid owns equity, even land. Lewis loves land. He’s thrilled when T. C. informs him he owns five and a half acres, not one and a half like he thought. “Good job, Dad,” he says.

The NIL dough has made Lewis’s transition to Boulder easier. “I’m living well out here,” he says. “A little more bougie.” His biggest headache at the moment is Smoke and his nonstop barking. But T.C. is on the case. He’s lined up a few prospects for dog trainers who will work with Smoke for free in exchange for a photo of Julian and his mouthy pup. He’s lining something up with Purina Pro Plan, too.

Back in Alabama, Trent Seaborn is focused on his big goal: leading the Thompson Warriors to another state championship. He says he’s not thinking about whether Representative Gray’s bill will pass. If it does, great. Maybe he gets rich. Maybe not. What matters most is what he does once the whistle blows. Even in the Wild West of high school NIL, the game is still king. Play it well, and you win.

Abigail Covington is a journalist and cultural critic based in Brooklyn, New York but originally from North Carolina, whose work has appeared in Slate, The Nation, Oxford American, and Pitchfork

esquire