Unfairly Traded Steel

Cleveland-Cliffs Chief Executive Lourenco Goncalves’s invocation of “unfairly traded steel” shows, a contrario, many reasons why free trade is an essential feature of a free society. Mr. Goncalves said that adding tariffs on steel products to tariffs on primary (semi-finished) steel provides (“Trump Leans on National Security to Justify Next Wave of Tariffs,” Wall Street Journal, August 28, 2020)

certainty that the American domestic market will not be undercut by unfairly traded steel embedded in derivative products.

He means that tariffs on primary steel do not suffice because imported steel-containing goods would gain an advantage over their domestically manufactured equivalents.

In passing, let’s note that in the roaring ’60s, it was popular among the ruling establishments of underdeveloped countries, supported by the Western intelligentsia, to impose large tariffs on foreign manufactured goods in order to help domestic manufacturing. Only when, a few decades later, it was realized that such an industrial policy was a fool’s errand, were the poor people of underdeveloped countries able to jump on the bandwagon of free trade and to escape dire poverty.

A basic economic reason why “unfairly traded steel” or the underlying ideal of mercantilist and industrial policy is a fool’s errand is that it presupposes a central economic planner possessing what he does not and cannot possess, that is, the information of time, place, costs, and preferences that is carried by prices determined by supply and demand on free markets. Friedrich Hayek explained that in the 1930s and 1940s (see Hayek’s American Economic Review article “The Use of Knowledge in Society”). A central planner cannot even know many intricate effects of his resource-allocation decisions, especially in a complex economy. Thus, government intervention begets government intervention in the greatest political disorder. That the US government only realized after imposing steel tariffs that they should be imposed on steel products too provides a rather funny illustration.

Another important lesson from protectionism—empirically confirmed a thousand times—is how rent-seeking special interests will try to exploit the general public, or part of it, each time the state offers them a means to do so. The requests for tariffs on steel-containing products are already flooding the government.

A related reason why an expression like “fairly traded steel” has no meaning but exploitative (or illiterate if not, truth be told, clownish) comes from a reflection on the value judgements that necessarily underlie public policy. Rational public policy recommendations require a justification in moral and political philosophy. If fairness is not defined in terms of individual liberty—if what is fair is not simply what is free—it is probably a smokescreen to impose on others the pursuit of the speaker’s self-interest. “Fairly traded steel” is what Mr. Goncalves thinks is fair for the interests of Cleveland-Cliffs’s shareholders besides his own self-interest. It is rare that an individual considers fair something that harms his own interests, and unfair a government subsidy or protection for himself or his organization. “Free” is much easier to define than “fair.” Liberty does not require that the whole world be made “fair” by somebody’s standards.

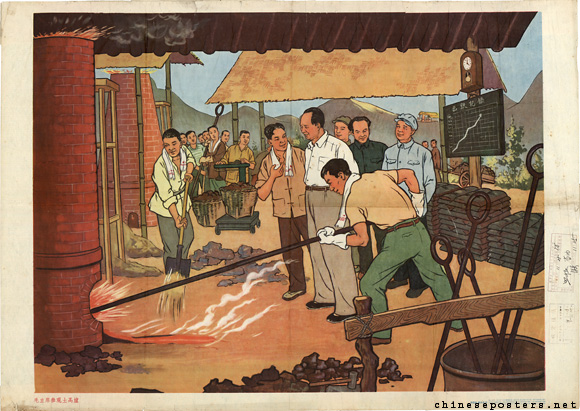

American steel companies have been protected off and on since the 19th century, and still think that fairness requires American consumers to be forced to pay more for steel products. How fair would it be that Americans be forced, in imitation of Chinese farmers in the heydays of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, to build little blast furnaces in their backyards? (See the featured image of this post.)

What happens to the interests of industrial purchasers of steel, consumers of steel products, and consumers of the goods or services that would be produced if fewer resources (workers, engineers, managers, machines, buildings, electricity, land, etc.) were forcibly diverted to the production of steel? Three ways exist to reconcile or adjust the interests of individuals living in society: customs (the tribe), command (the coercive economic planner or dictator), or the market (free and voluntary cooperation). An interesting and easily accessible book on this is John Hicks, A Theory of Economic History (see also my review in Regulation).

Both historical experience and economic theory teach that an efficient reconciliation of individual interests—“efficient” meaning that it maximizes the formal opportunities of all individuals—can be accomplished by free markets, but not by the diktats of the central planner and his court of lobbyists and sycophants.

We are thus led to discover that “unfairly traded steel” could only make sense in a society where a dictatorial or collectivist political regime imposes on everybody some arbitrary conception of fairness. The alternative is reciprocal individual liberty, of which a manifestation is free trade, internal and external, between individuals or their private organizations. (James Buchanan’s little book Why I, Too, Am Not a Conservative offers a reflection on reciprocity; I reviewed it in Regulation.)

******************************

Chairman Mao visits a homemade blast furnace, 1958 Credit: PC-195a-s-013 (chineseposters.net, Private collection)

econlib