Her son died of asthma. Now kids get lessons on surviving smoky skies, in his name

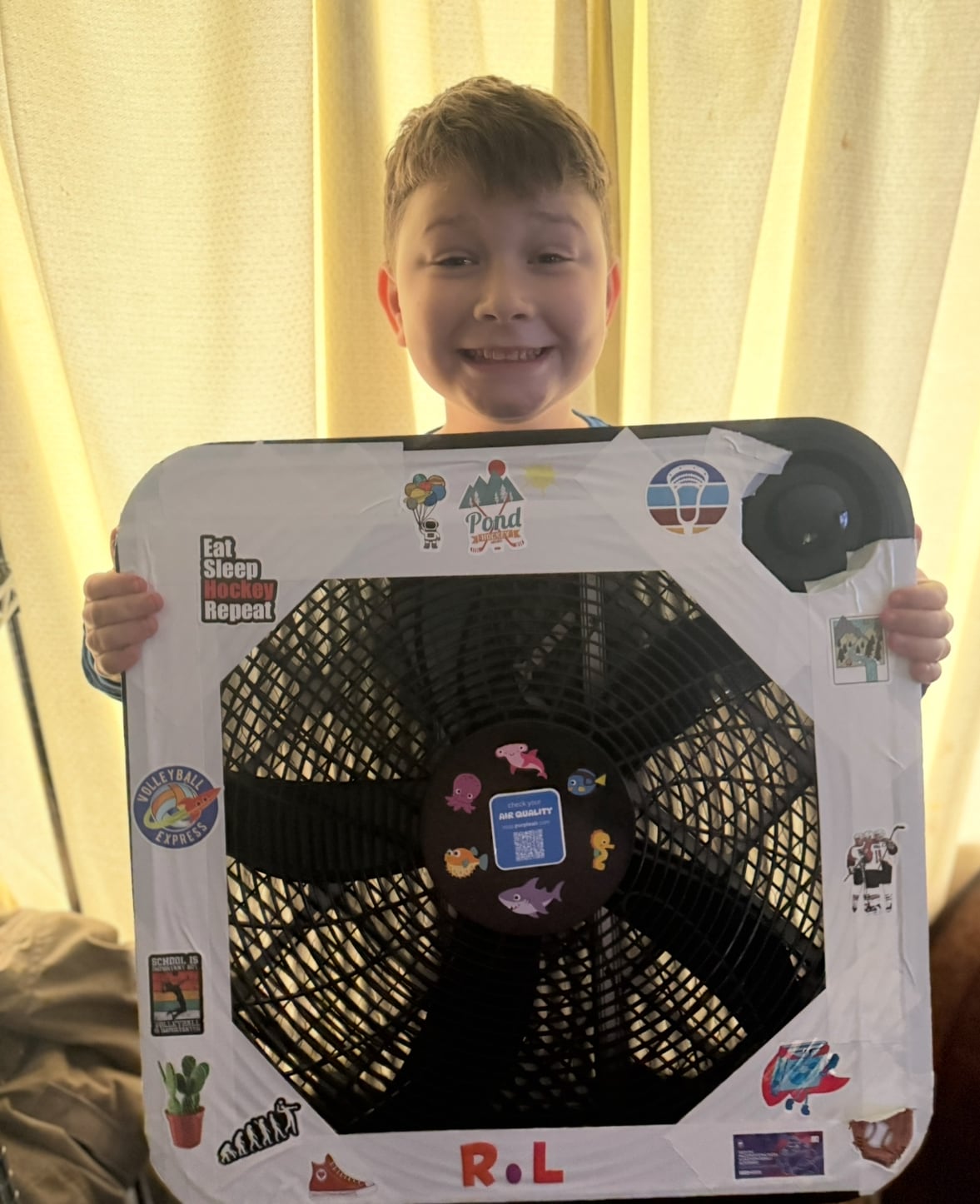

Every day, nine-year-old Roland Latimer checks the air quality in Gold River, B.C., before heading outside. He has asthma and carries puffers to help him breathe.

When air quality is poor, like when wildfire smoke is present, he’s forced to stay indoors.

Wildfire smoke is dangerous for everyone’s health, but for Roland it can trigger a dangerous asthma attack. Even though it’s for his safety, he finds being stuck inside frustrating.

“It feels like I'm trapped,” he told What on Earth host Laura Lynch.

Having access to local safety information — with four air quality monitors now in the small Vancouver Island village where he lives — is part of the legacy of a B.C. boy who died from an asthma attack during the wildfire season in July 2023.

Carter Vigh, also nine-years old, went to a birthday party at a water park on a day his parents say they couldn’t smell smoke. The Air Quality Health Index reading was “low risk,” they recall, but that was based on air quality monitors around 100 kilometres away from their home in 100 Mile House, B.C.

His mother, Amber Vigh, wants to turn that tragedy into an opportunity to help others, so the family has partnered with the B.C. Lung Foundation to create Carter’s Project.

“We need to take the time and learn about air quality and how important it is,” she said.

Wildfire smoke can be dangerous, even when we can’t see or smell it.

It contains gases and tiny particles, known as PM2.5, that get deep in the lungs and cause inflammation. For at-risk groups, like seniors, young children, and people with chronic health conditions like asthma or heart disease, it’s more hazardous.

In 2023, the summer Carter died, Canada’s record-breaking wildfire season caused an estimated 5,400 acute deaths and 82,100 premature deaths worldwide, according to a study published last month in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

But Vigh believes people have become complacent when it comes to air quality.

“We've decided that now we have a wildfire season and it's just the norm that it's smoky for a couple months.”

Now, the B.C. Lung Foundation and Carter’s Project has provided 20 outdoor and 200 indoor air quality monitors to schools and communities, including 100 Mile House, Gold River and Dawson Creek. They’re also going into classrooms — like Roland Latimer’s — to teach people about the importance of air quality so they can keep themselves safe.

Vigh worries that if they didn’t take initiative, nobody would’ve.

“We're going to be the change that's going to bring this topic forward,” she said. “These things could happen on a grander scale if the government would step in and help us but it's pretty rewarding to know that we are making sure that it's happening.”

The B.C. government says it has invested more than $300 million in HVAC system upgrades to support better air quality and ventilation projects at hundreds of schools in the province.

In a statement sent to CBC, B.C.’s Ministry of Education and Child Care said the science curriculum covers topics like the respiratory system and Earth’s atmosphere, which could be used to explore issues like air quality and its impacts.

The ministry is working with the province’s Climate Action Secretariat to develop resources to support teachers with climate change lessons. But they’re not considering reviewing or revising the curriculum.

‘Scientists in their own community’B.C. Lung Foundation President Chris Lam says most people take the air for granted. He wants to work towards normalizing conversations about air quality.

“Our goal with this project really is to empower people. Let people become scientists in their own community. Measure what's in the air and they get to take action,” Lam said.

During the B.C. Lung Foundation's information sessions, they also show people how to make do-it-yourself air cleaners that filter fine particulate matter, a technique developed with the B.C. Centre for Disease Control during the pandemic.

Lam says air quality monitors and purifiers can save lives. He says his organization is dedicated to providing those options schools, even if they have to go one classroom at a time.

Lam believes learning about air quality should be accessible and happen at school, whether in a science class or a workshop, for example. He says students should know what the air quality index numbers are, what makes them change and how air quality can affect them.

“If we're able to educate kids and make it really fun and accessible, it really does start to spread out,” he said.

Melissa Lem, a family physician and the president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the environment, says discussions about wildfire smoke risks have to be paired with solutions or people will feel overwhelmed and anxious.

For example, when the Air Quality Health Index is higher than four, Lem suggests staying indoors with an air purifier running or wearing a mask or face covering outside if you have to go outside.

“I think we need a better understanding in general, that we need to be more careful at lower levels of air pollution,” she said.

Lem pointed to an opinion article written by B.C. Centre for Disease Control doctors which noted that although extreme concentrations of PM2.5 and smoky skies get a lot of attention, more harm is done at the lower concentrations that occur more often.

Chronic and repeated exposure to air pollution is a huge concern because long term effects build up, Lem says. She hopes there’s more education around the risks and how people can protect themselves.

“In Canada, because it's only recently that we've been exposed to more and more air pollution, we're not as aware of it,” she said. “Carter's Project is an important way to raise awareness about it, especially among children and young families.’

‘He was a boy just like me’Vigh says sharing her family’s painful story is an effective teaching tool because it makes the problem appear more real than something in a book or a YouTube video.

“We're telling the real life story of what can happen if we're not cautious and teaching people how to be cautious and how to keep themselves safe,” Vigh said.

She says hearing about Carter resonates with students because he died so young.

Roland said he was “sad and scared at the same time” when he heard about Carter’s death.

“He talks about Carter all the time and he tells people about him too,” Roland’s mother, Tricia Latimer, told CBC.

“He says, ‘I didn't know him, but he was a boy just like me.’ He realizes how severe it is, and that it could’ve been him.”

Vigh says she’s proud of the legacy her son left and proud of Roland for carrying the torch and helping to spread Carter’s message. Vigh says Carter’s Project gives her hope.

“When you lose a kid, there's so many pieces of your heart that are broken and missing, but this project has helped to bring my heart back together.”

cbc.ca