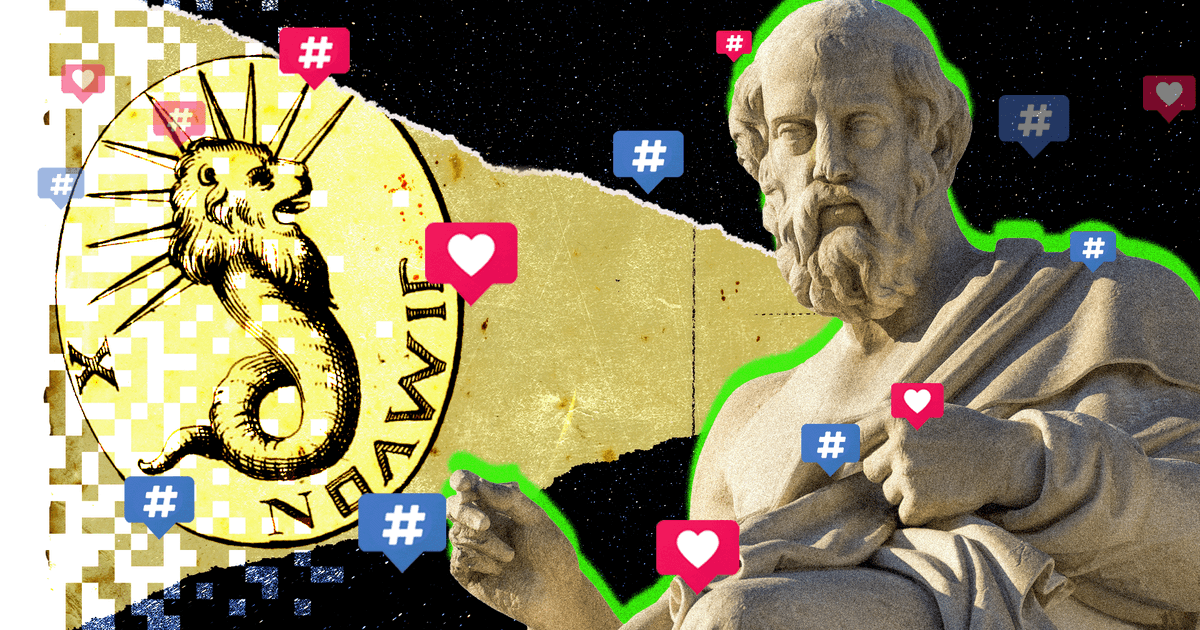

From Plato to TikTok: how online forums transformed the myth of the demiurge into a meme.

On social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, videos and illustrations of a curious figure have been shared tens of thousands of times.

With a lion's head and a snake's body, the "character" occasionally appears alongside other memes and popular internet figures, such as the football influencer Luva de Pedreiro and Davi Brito, a former participant in the reality show Big Brother Brasil (BBB).

Generally, the content mixes absurdist humor, melancholic music, philosophical phrases, and that curious figure.

This refers to the "demiurge," an age-old idea that is now being reinterpreted on the internet.

The "demiurge" emerged in Ancient Greece, in the work of the philosopher Plato, as a god who organized the world.

Later, it was reinterpreted by Gnosticism, a movement in the early centuries of Christianity with branches that still exist today.

On the internet, it resurfaced about a decade ago in forums like 4chan and in red pill communities (groups that exalt masculinity, often misogynistic).

In recent months, the demiurge has broken through the bubble to reach the most popular social media networks.

"It's a meme about 'being trapped in this horrible world.' It's an internet joke, but it appropriated an idea to express a contemporary feeling," explains Luciane Belin, a researcher at NetLab (Laboratory for Internet and Social Network Studies) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

So, who is the demiurge?

The word "demiurge" comes from the ancient Greek dēmiourgos , which means "craftsman" or "public worker".

The figure originated in the dialogue Timaeus , written in the 4th century BC by the philosopher Plato.

The demiurge appears as a kind of cosmic craftsman responsible for shaping the universe.

Unlike a creator ex nihilo — a Latin expression meaning "from nothing" and which designates a God who creates the world without pre-existing matter — the Platonic demiurge works with pre-existing, chaotic, and disordered matter, which he organizes.

In Platonic philosophy, there is the sensible world, where humans live; and the world of Ideas, perfect and eternal, where the true essence of things reigns.

Inspired by the world of Ideas, the demiurge's power shapes sensible reality to make it as beautiful, rational, and ordered as possible.

Plato stated that he wished "that all things were good and nothing were bad".

Thus, the Platonic cosmos is the result of a benevolent act, albeit limited by the imperfection of matter. In this context, the demiurge appears as a positive figure, a symbol of harmony and order.

This connotation of the demiurge began to change in some segments of Gnosticism, a set of religious traditions from the 2nd and 3rd centuries that reinterpreted elements of Christianity and Hellenic philosophy (currents that succeeded Plato, from the period between the conquests of Alexander the Great in 336 BC until 30 BC, when the Roman Empire dominated Egypt).

In texts from this period, such as the Apocryphon of John and the Hypostasis of the Archons —probably written between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD, rediscovered in the Nag Hammadi library in Egypt in 1945—the demiurge appears as an arrogant and ignorant being, often identified with the God of the Old Testament.

Known as Yaldabaoth or Saklas, he is described as the ruler who imprisons human souls in corrupted bodies and material worlds, distancing them from true divinity.

At the end of the 2nd century, Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon wrote the work Adversus Haereses ("Against Heresies").

His goal, as one of the first theologians of the Catholic Church, was to denounce and refute what he considered "heresies" that threatened nascent Christian orthodoxy—that is, to attack other currents, including Gnosticism, in order to defend and propagate Christianity.

In this book, Irenaeus describes his view of how different Gnostic groups understood the demiurge: not as the good God, but as a lesser deity.

According to Irenaeus, these groups believed that true salvation did not depend on faith in the incarnation or resurrection of Christ, but rather on gnosis—an esoteric knowledge that allowed human beings to awaken the divine spark imprisoned within themselves and thus return to the divinity that lies beyond the demiurge.

GnosticismThis idea is not shared by contemporary Gnosticism in Brazil, says Marcus Bonassi, one of the volunteer representatives of the Gnosis Brazil Institute.

The organization is present in all state capitals, has more than 100 offices, and approximately 3,500 active members, according to Bonassi.

He says it's a mistake to classify Gnosticism solely as a religion.

"It's much more a way of thinking, a logical understanding of things, that completely changes the way you reason," he says.

The foundations of contemporary Gnosticism stem from the principles disseminated by the Colombian Samael Aun Weor (1917-1977).

He spread his ideas throughout the United States and several Latin American countries in the 1950s.

In his first book, published in 1950, Perfect Matrimony , he asserted that sexual energy was the most powerful force in nature and that, if channeled "correctly," it could lead to spiritual awakening and the attainment of gnosis.

Orgasm would be a dissipation of vital energy, and gnosis would require redirecting it to other activities, such as meditation.

Historians of religions point out, however, that this branch is syncretic (combining different beliefs and/or worldviews), not necessarily faithful to the Gnosticism of the first centuries.

In his doctoral thesis, presented in 2022, theologian Luiz Antônio Pinheiro defined Gnosticism as a syncretic movement of a philosophical, religious, and initiatory nature (involving initiation rites).

According to Pinheiro, Gnosticism has been able to survive for centuries, even to this day, due to its "enormous capacity for adaptation to institutions, religions, and social groups."

The movement also managed to survive the various persecutions throughout the centuries because it was practiced "in small groups, without drawing attention or acting discreetly," wrote the theologian in his thesis, presented to the Jesuit Faculty of Philosophy and Theology in Belo Horizonte.

From history to online forums

A new reinterpretation of Gnosticism and the demiurge took place online — and even before TikTok.

Starting in the 2010s, these concepts circulated in forums such as 4chan and Reddit, where they were associated with conspiracy theories, ideas of manipulating reality, and discourses critical of modernity.

In these communities, the demiurge appears as a metaphor for "corrupt systems" or "hidden programmers" that control social life.

Esoteric ideas were also appropriated, within the forums, in the metaphor of pills , born with the movie Matrix (1999).

In it, the protagonist Neo can choose between taking the blue pill and remaining in the comfortable illusion, unaware of the true reality; or taking the red pill and awakening to the harsh, hidden, and painful "truth."

On the internet, "red pill" has come to symbolize "waking up" to a supposed hidden truth—especially in the "machosphere," it has become a philosophy with misogynistic ideas that rejects egalitarian gender values.

Men are classified by pill colors according to their relationship with the world and with women — the blue pill would be those who remain compliant with the "system" and submissive to them.

In online forums, an ironic variation of the pills emerged: the green pill , which alludes to Gnosticism and other philosophical and esoteric ideas.

In this universe, the character Green Pill sees the world as a prison ruled by the demiurge—and true awakening would consist of recognizing that reality is manipulated by this force.

Thus, adherents of the green pill , by turning to philosophical and spiritual questions, would simply ignore the "reality" seen by red pill adherents, who frequently mock this stereotype.

Luciane Belin, a researcher at NetLab/UFRJ, explains that this type of appropriation is part of a broader logic of reusing old symbols in digital subcultures.

"Symbolic aesthetics serve to create a kind of identity cohesion, marking boundaries between who is inside this group and who is outside."

In this context, the demiurge detaches itself from its original Gnostic meanings, becoming a rhetorical device.

"These communities use philosophical language, flirting with the question of religion in a certain way to give intellectual and spiritual authority to their discourse. This appropriation of ancient symbols gives a kind of veneer of depth," says Belin.

According to Marcus Bonassi, the viral spread of the demiurge distorts the original meaning of this figure for Gnosticism — which, he points out, does not "anthropomorphize" (represent as a person) the demiurge.

"It is a force that acts in nature and the universe, including within the human being, which has the capacity and responsibility for creation. Gnostically, good and evil do not exist. The demiurge is the representation of the three forces of creation—father, son, and Holy Spirit, or Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva in Hinduism, or even proton, electron, and neutron in science."

"When a person does something they don't understand, they play around with anything. In my view, they don't know what they're doing," laments Bonassi, referring to the appropriation of the demiurge on the internet.

Now, by breaking through the bubbles of online forums and becoming more popular, the demiurge appears as a kind of villain in memes: someone tries to escape the imperfect world we live in through gnosis, and is prevented by it.

He also "co-stars" with other memes and personalities.

Many of the videos are made using artificial intelligence (AI) and have a lo-fi look, a typical internet aesthetic that manipulates vintage elements (with an old and/or classic appearance).

In the comments, it's not uncommon for internet users to question what the demiurge is or where the meme came from.

Luciene points out that, in the laboratory's surveys, the demiurge appeared in a still limited way, but linked to nonsense memes and pessimistic and self-deprecating content.

Thus, the meme captures a part of the social climate.

"It's not just men in the macho sphere who feel these things. If you think about it, it's a whole issue of capitalism itself. We're really trapped in this horrible world," says the researcher, laughing.

BBC News Brazil - All rights reserved. Any reproduction without written authorization from BBC News Brazil is prohibited.

BBC News Brazil - All rights reserved. Any reproduction without written authorization from BBC News Brazil is prohibited.

terra