Intellectuals on vacation. But the novel-like summer no longer exists.

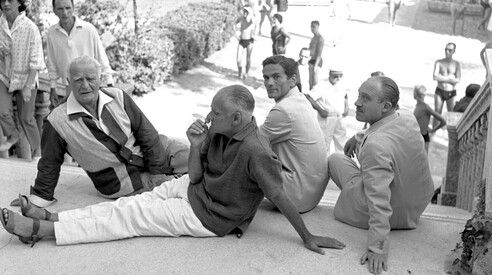

Leonida Repaci, Moravia, and Pasolini in 1968 (Getty Images)

Tell me where you're going

For a while it was Capalbio, once it was Sabaudia with Moravia and PPP. But the idea of vacation is changing, also due to the devaluation of the creative class and the power of paper. Goodbye, twentieth-century slowness.

Just as there are simplified maps for children to learn about animal habitats—the polar bear in Greenland, the penguin in Antarctica, the kangaroo in Australia—we could make a map with the faces of intellectuals who go on summer vacation. We could create an atlas of the "Athens of Italy," we could illustrate a topography of the holiday homes of writers, both men and women, who in the heat move to mountaintops or along the coast, carrying bags of books and inviting international guests and penniless admirers. The summer months for those who write and think are different, or at least they were, from those who occupied themselves with other pursuits in life. The intellectual, despite himself, never stops working, as Joseph Conrad's oft-used question reminds us: "How can I explain to my wife that while I'm looking out the window I'm working?" And so there's no need to explain to publishers, directors, editors, and friends that while you're on the beach, while you're watching the wake of the ferry heading to the Aeolian Islands, or while you're walking in the woods of Abruzzo, you're somehow working.

Forte dei Marmi has also been the cradle of formidable writers, from Longhi to Malaparte, who even wanted to open a super chic bar there.

The intellectual is never truly on vacation. The world of culture is like a perpetual machine, always in motion, defying the laws of thermodynamics. Nulla dies sine linea, as Pliny the Elder said, "not a day without jotting down a sentence," even when waiting in line at the gate. Even an excursion, a trip, a pilgrimage, a journey can be an opportunity—indeed, they become one—to gather thoughts on your iPhone, or even a book to be published the following summer. But an exotic vacation, a trip abroad, must be differentiated from a twentieth-century Italian holiday. And there are places that, for geographical convenience—namely, proximity to Rome or Milan—attract men and women of thought, but also for their natural beauty, or a passing fad, or simply to be close to friends who have bought a house there. Places like Capalbio, for example, "the kingdom of the radical chic," as Flavio Briatore quirkily calls it, now synonymous with the holiday clique worthy of a Virzì film. And then the less paparazzi-heavy Montemarcello, where Natalia Aspesi, Franco Fortini, and Indro Montanelli had homes, and where the critic Antonio D'Orrico and various editorial circles still meet. Or the eternal Forte dei Marmi, now a refuge for Russian oligarchs (in plain clothes), Saudi princes, and Milanese scions, but which has long been the cradle of formidable writers, from Roberto Longhi to Curzio Malaparte, who even wanted to open a super-chic bar there, Chez Malaparte—Versilia is found in so much literature, celebrated in Arbasini's Piccole vacanze (Little Holidays) and in the bestseller of the ladies, Vestivamo alla marinara (We Were Dressed in Sailor Clothes). Among the places that, like these, end up on the map, also and above all by virtue of being hangouts for intellectuals who escape the thirty-seven-degree heat of the city, Sabaudia certainly deserves mention in Italian cultural history. And if we were to draw a map like those for children, Sabaudia would feature Alberto Moravia's face, with his iconic eyebrows and elegant clothes even on the shore.

Paolo Massari recounts Sabaudia in "The Intellectuals' Holiday." Moravia and Maraini write and cook, while Pasolini goes on a romp.

In the province of Latina, Sabaudia, a town on the Lazio coast, was long the stronghold of the author of "I Indifferenti" and his gang during the last century, attracting more and more "insiders" over the years. It's ironic that the left-wing, Rome-centric intelligentsia of the late twentieth century had established its outpost in a town built by the Mussolini regime, a bit as if the Capalbio of the early 2000s had arisen on the ruins of a rural Milan 2. Il Duce had laid the foundation stone in August 1933, filmed by Istituto Luce cameramen, and La Stampa celebrated a new village "in the land already cursed by the centuries and restored to His genius by human labor." Sabaudia, built in a very short time, was designed by the architects of MIAR, the Italian movement for rational architecture, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti contrasted the new village with the "sewn and patched villages" that dot the peninsula. Also on the commission was Adalberto Libera, who, with Malaparte, designed the overhanging villa on Capri, perhaps the most famous holiday home of all time. When writer Sibilla Aleramo visited Sabaudia and the reclaimed Pontine Marshes, she described the large mascellone as a "gigantic miracle-worker" that would go down in history, if only for this reason alone: for having given rise to urban centers, populated first by settlers and then by writers, where there were only mosquitoes and malaria. It's no coincidence that many nostalgic for the regime today use the story of the reclamation as the first rule of "Mussolini also did good things," like Sabaudia, for example.

But let's return to the very Roman Alberto Moravia, who, partly to be close to his hometown, discovered this stretch of coast and fell in love with it. One day, he was introduced to it by the largely forgotten painter Lorenzo Tornabuoni, who had a house there that Moravia liked because it reminded him of Japanese homes. And so the writer slowly decided to build a house there too, involving his friend Pier Paolo Pasolini, as well as his partner Dacia Maraini, with whom he had taken up residence after separating from Elsa Morante. In the 1970s, they built this little house among the dunes, which Pasolini would only enjoy for a short time, just one summer, as he died in 1975. When Moravia speaks of Sabaudia, he goes back in time, before the 1920s, and links the place's significance to Ulysses's voyages and the nearby promontory of Circeo, a land said to have been inhabited by the sorceress who transformed her companions into pigs. For Alain Elkann, the profile of the promontory seen from the beach resembles Moravia's face, like "a gigantic sculpture" of the writer. Elkann also knows that sand well, because for a period of time he will go to Moravia's house every day, recording and transcribing conversations with the writer for a major biography, which will be published after Moravia's death. Often, because of the heat, they are forced to sit shirtless at the table, and every now and then Moravia wants to abandon the project, annoyed by the questions. The two even argue over whose name should be put first on the cover. Elkann defends the alphabetical order. Moravia replies: "But I'm Moravia!"

In Sabaudia, the club helps to remove the Mussolini flavour from the city which, even architecturally, was so despised by the left

There, in the house among the dunes, as they call it, among the verandas, the white façade, and the terracotta floors, dinners and spaghetti dinners are hosted with friends from the Roman circle: Laura Betti, Elio Pecora, Raffaele La Capria, Enzo Siciliano, the poet Dario Bellezza, Ninetto Davoli, Piera Degli Esposti. And then Giovanni Comisso, who had a house nearby, in San Felice, and even some members of Gruppo 63, and Ingeborg Bachmann, who frequents Circeo, and even Jean Genet, visiting, who tries to draw Moravia into the Palestinian cause, there among the August waves and the juniper bushes (Moravia withdraws). A place different from other tourist destinations within reach of the capital, as Edoardo Albinati says, Sabaudia is "wilder," and inspires "a sense of wilderness." Moravia, along with his roommates Dacia and Pier Paolo, had a fairly strict routine there: he rose very early in the morning, wrote until eleven, and then walked a few kilometers to the town square where he discussed the price of the fish they were cooking for lunch with the fishmonger (Moravia, many say, was careful with his money). La Capria would later recall in one of his writings the annoying clatter of the typewriter keys in the morning, him waking up in search of coffee while the other had already written who knows how many pages. Today, Paolo Massari recounts all the details of the Via Veneto holiday on the Lazio coast in his book The Intellectuals' Holiday. Pasolini, Moravia and the Sabaudia Circle (Utet). The cover features a photo of Moravia on the beach, wearing a shirt, sweater, and long pants—and the ever-present silk scarf—staring at the horizon and frowning in thought. He's sitting on a bamboo chair, and it's instantly a meme, a symbol of the Parioli-like, Dostoevskian existentialism of the author of Agostino. While Moravia and Maraini write and cook (and Moravia washes the dishes), Pasolini uses the house more as a base for his amorous escapades. Late at night, starting from the EUR district, he arrives there, and then, as his friend Moravia recounts, he goes out "every evening on homosexual incursions along the entire coastline, between Ostia and Terracina," and sometimes he can be heard returning home in the dead of night, "furtive as a wolf." Pasolini and Moravia help to remove the Mussolinian flavor from the fascist city, which, even architecturally, was so abhorred by the left, and transform it into friendly territory, fostering the appreciation of rationalism. Pasolini embraces Sabaudia's "architecture of a fascist nature," finding it "something between the metaphysical and the realistic," reminiscent of De Chirico's paintings. He thus seeks to separate it from the experience of the twenty-year period, with its usual intellectual protective mechanisms, saying that, deep down, yes, it is "a ridiculous, fascist city," but that "it suddenly seems so enchanting." Why? "Because there's nothing fascist about it," and in reality its beauty is owed to the "reality of provincial, rustic, paleoindustrial Italy."

And so others arrive there, or at least other authors are more willing to frequent that stretch of sand in Lazio, no longer "dirtied" by the history of the twenty-year period. Monica Vitti rents a small house. And so does Bernardo Bertolucci, whose father, the poet Attilio, was a great friend of Moravia. The Parma-born director loved Sabaudia partly because the surrounding countryside reminded him of his native Emilia. He decides to buy a house in the area, where in 1978 he shoots his film La Luna. "Sabaudia had become beautiful," he writes. He's set up an editing room in an outbuilding. There, one deserted winter, he also hosts the English writer Ian McEwan, called to write the screenplay for a film based on Moravia's book 1934, which will never be made. In an interview with Nuovi Argomenti, the director recounts that it rained every day. We took long walks on the beach like certain intellectuals in French New Wave films. I wanted to turn 1934 into a comedy, don't ask me why. Luckily, at the same time I was reading the autobiography of Pu Yi, the Last Emperor…

"Sabaudia represents a happy period in my life," Dacia Maraini tells Mossato, between "days of intense writing and a life at the seaside." Summers spent among bikini-clad Frenchwomen, working-class suburbia residents, editorial writers for L'Unità, and young assistant directors, among Monicelli, Félix Guattari, and Del Giudice, gatherings of friends, baked fish, and Campari soda before dinner—scenes that immediately evoke nostalgia for the days when intellectuals did just that, and could live without a penny if they wanted, or could enjoy a bit of the Spartan bohemian aesthetic of a nude beach and a wicker sofa by abandoning the bourgeois apartments on Lungotevere della Vittoria for a few months. Just as Capalbio votes right, today Sabaudia is no longer the holiday cradle of Rome's cultural elite, although Roberto d'Agostino, Carlo Verdone, and Francesco Totti, the ideal Roman triumvirate, still have homes there. Maps are changing, and the idea of vacation is changing, partly due to the devaluation of the creative class and the power of paper. Once upon a time, Moravia wrote for L'Espresso; today, we're writing for "digital marketing" influencers like Marco Montemagno (who presents himself as a "self-entrepreneur"). And so, between overtourism, the professional crisis, and global warming, long-term intellectual vacations are disappearing, the slow pace of 20th-century summers is gone, and freelancers must invoice even on August 15th. At most, they hop from one festival to another—there are thousands of them—to recreate temporary gatherings, temporary cliques, for an evening or two, on a second-class train paid for by the organizers, presenting and trying to sell their book or their face. Unfamiliar places with oratory chairs in a small square that attract women after dark, to listen to the presentation of a novel or essay, whether on Renzi, Gaza, or Socrates. The important thing is to get out of the house and do something, hoping for a nice breeze. For some reason, the return of illiteracy is increasing in parallel with the number of literary festivals. Fedez going to sing at the dried cod festival in a small town in Calabria is a sign that this is extending to other worlds as well, and that the slow summer of Gianfranco Calligarich's or Arbasino's or Cesare Pavese's novels no longer exists. In short, Moravia no longer lives here.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto