Some spending years in N.B. psychiatric beds because housing options scarce, says ombud

A psychiatric patient lived in a Campbellton hospital for more than 20 years before an intervention from the New Brunswick ombud led to her finding a home in the community for the last few months of her life.

That was just one example of a patient living in psychiatric care for far longer than necessary, an investigation by Ombud Marie-France Pelletier has found.

Her latest report calls that patient "Isabelle," and says she was left in restraints at the Restigouche Hospital Centre for extended periods on a daily basis. The ombud began to work with Social Development on finding Isabelle a placement, and eventually she was moved out of the hospital and into a care home.

"Once there, she was able to enjoy more social interactions with her family and peers," the report says.

"Isabelle passed away a few months following her transfer in the community. Nonetheless, her family was grateful for an improved quality of life in her final months."

Interviews the ombud's office did with hospital staff across the province found that psychiatric patients are typically waiting a year or longer for a community placement, to give them a home outside a hospital setting.

"Staff explained that if a placement is not found, Social Development often closes the patient's file. This means that resources are no longer actively looking to find the patient a community placement," the report said.

Pelletier said patients with complex needs, such as an intellectual disability or developmental disorder, are often admitted to a hospital when they display difficult behaviours, including aggression, because there's nowhere else for them to go.

CBC News has also followed the story of Devan Tidd, an autistic man who was held at a federal prison under an agreement with the province after he spent nearly a decade at the Restigouche Hospital Centre.

The New Brunswick Review Board recently granted him a discharge into the community, but during the hearing about that discharge, Tidd's psychiatrist noted that "it may take at least several months" to find a place for him to live.

Minister of Social Development Cindy Miles did not answer a question from CBC News about why that delay is happening.

Housing New Brunswick has opened seven new public housing developments this year, including two supportive housing complexes in Moncton. Further discussions are underway to see if additional spaces like those can be added in the near future.— Email from Social Development Minister Cindy Miles

But she sent a statement saying her department is working with N.B. Housing to add more options.

"Housing New Brunswick has opened seven new public housing developments this year, including two supportive housing complexes in Moncton," she said in an email.

"Further discussions are underway to see if additional spaces like those can be added in the near future."

Child, Youth and Seniors advocate Kelly Lamrock also recently called on the province to address the current "lack of moral clarity" when it comes to housing for people with disabilities.

"We're following with a lot of interest the case where we've got somebody, where they've carved out a place in what should be a correctional institute," he said. "I think there have to be some lines we will not cross."

'Stuck in the system'Unnecessary hospitalization puts a strain not just on patients but also on psychiatric staff, according to Sébastien Lagacé, the associate vice-president of mental health and addiction at Vitalité Health Network.

"The role of the staff is to treat them to make sure that they can reintegrate [into the] community in a timely manner," Lagacé said in an interview. "It's difficult for employees to see patients being stuck in the system and not being able to flourish in society."

Pelletier also flagged the impact on the health-care system.

"Overcrowding in psychiatric units can cause challenges throughout the hospital, with new psychiatric patients waiting to be admitted and taking up space in emergency rooms," she wrote.

We have around 40 per cent of our patients at the Restigouche Hospital Centre that have a discharge, but there's no space in [the] community to accept them.— Sébastien Lagacé, Vitalité Health Network

Lagacé said the rental and housing market can be challenging for patients, due to the stigma of having been hospitalized for psychiatric care.

"We have around 40 per cent of our patients at the Restigouche Hospital Centre that have a discharge, but there's no space in [the] community to accept them," Lagacé said.

"The fact that they've been into a psychiatric institution creates a barrier for them to reintegrate [into] society."

He welcomes the ombud's call to the province to boost the availability of housing for people with complex mental conditions.

Financial implicationsJulia Woodhall-Melnik is a part of a housing research study designed to produce a national scan of housing options for those with chronic mental conditions.

When members of the group went to examine New Brunswick's high-support options, she said they discovered there were none.

"Actual high-support housing options for folks with mental illnesses, we don't have them in the province," Woodhall-Melnik said.

"So right now what you're seeing is a lot of folks falling through the gaps, folks who are unhoused, who would rather be unhoused than housed in a psychiatric facility when they don't really need to be there, or folks who are in... long-term care that don't require it."

Woodhall-Melnik said housing research shows "time and time again" that leaving the issue unaddressed will cost the province more in the long term than acting to solve it.

"The financial implications are devastating, right? The most expensive form of care is hospital care ... the dollars and cents don't make sense there," she said.

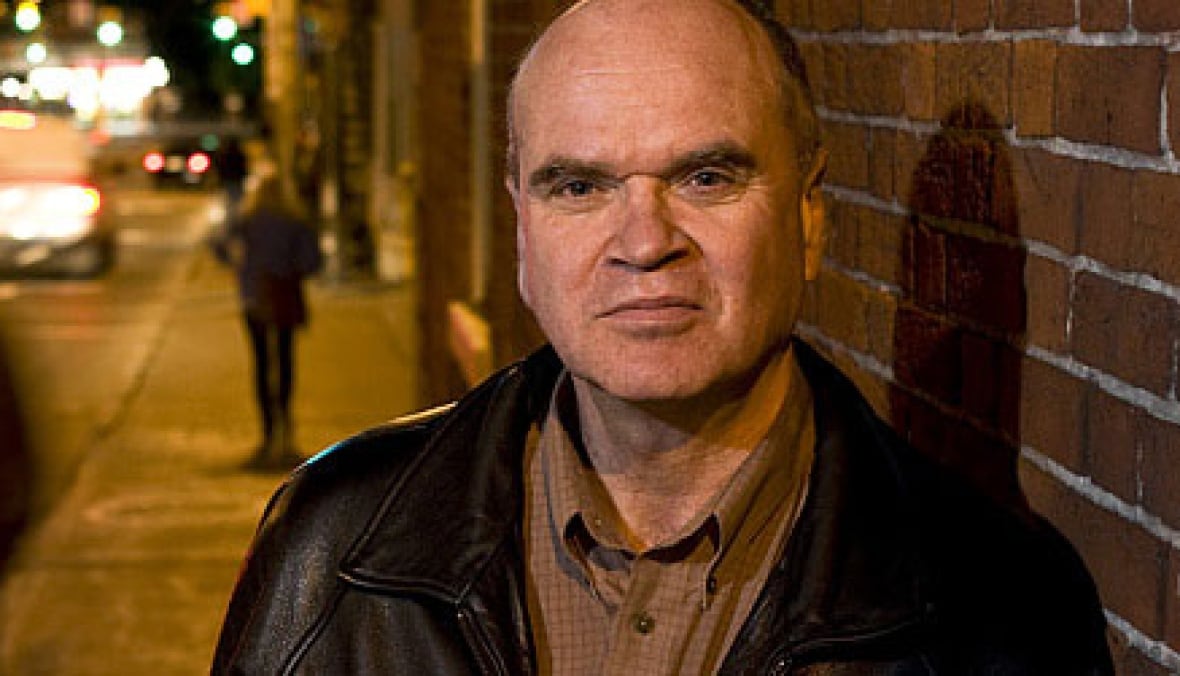

'A question of priority': ExpertThe province also recently struck a task force to study homelessness, although University of Ottawa professor emeritus Tim Aubry said there are already known solutions.

A decade ago, Aubry led the At Home/Chez Soi project in Moncton, which studied supportive housing options for people with mental illness.

They found that housing with wraparound services — in their case, a mobile team of health-care providers — was key to a person's recovery, along with rent supplements.

"The improvement that they experience gives them a chance, if it's there, to start to build a life despite, you know, maybe the continuation of mental health symptoms," he said.

"It's the idea that they can go beyond their illness and pursue things that... are important to them."

He said regional health authority Flexible Assertive Community Treatment (FACT) teams, which aim to reduce hospital stays for patients with severe mental illnesses, were used with study participants.

Those FACT teams still exist today, but Aubry said governments still seem to struggle with combining health and housing resources to execute the kind of model his team worked with.

Aubry believes pairing these FACT teams with tenants living in supportive housing units would be an ideal path forward.

"It's a question... of priority... Where do you put your resources?" Aubry said.

"Because of the visibility of homelessness all across the country, it's not hidden anymore. You've got encampments in most cities, big and small, and it's a reflection of really a failure in our social policies and health policies."

cbc.ca