When yogurt fermentation becomes a matter of ants

Live red ants to make yogurt? Yes, you read that right! These tiny workers provide both the precious bacteria and the essential acids to kick-start fermentation. Would you be willing to dip your spoon into yogurt fermented by very real ants? Whatever your answer, a team of Danish and German researchers has just unveiled one of the most surprising and offbeat practices in food history: using ants as fermentation agents, a subject at the crossroads of ancestral traditions, gastronomy, and microbiology.

To uncover the secrets of a recipe still practiced in Turkey and some Balkan countries, anthropologists, chefs, and food scientists traveled to Nova Mahala, a Bulgarian village, to revive an ant yogurt using local methods. Their study was published on October 3, 2025, in the online journal iScience .

For the experiment, they chose freshly collected raw cow's milk and red wood ants (Formica rufa) , collected at the edge of the village. The milk was heated to near boiling point, at a temperature such that it "bite the tip of the little finger." Four ants, still very much alive, were immersed in 400 ml of milk. The mouth of the jar was covered with cheesecloth and the whole thing wrapped in a cloth to maintain the thermal softness.

The whole thing was then buried in the heart of the anthill, completely covered by the nest material. The latter, thanks to the heat it naturally gives off, transforms the colony into a living incubator, perfect for stimulating fermentation. The jar was recovered after 26 hours of incubation.

In this process, the ants act as the inoculum, while the anthill acts as a natural incubator. At this stage, the acidity, texture, and flavor of the mixture evoke the very first steps of a yogurt in the making: the milk had acidified to a pH of 5, coagulated at the bottom of the container, and revealed "a slightly tangy taste, with herbal notes."

A Danish restaurant teeming with new ideasBefore discussing the biochemical and bacteriological results of the study in detail, it is worth highlighting the active participation of the research and development team at the Alchemist restaurant in Copenhagen. They distinguished themselves by concocting daring culinary creations made from ants.

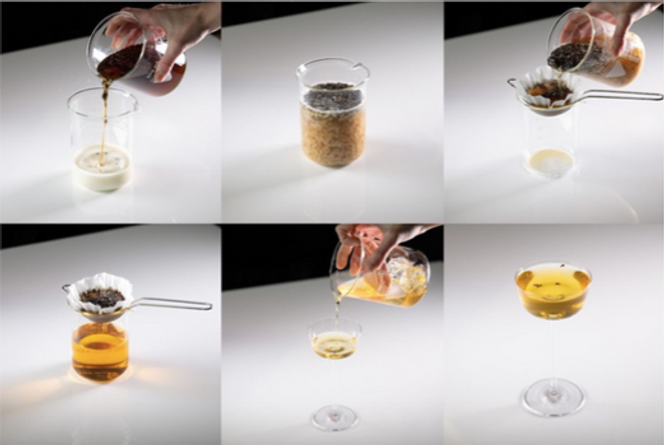

Ranked fifth in this year 's World's 50 Best Restaurants and awarded two Michelin stars, this establishment is not lacking in inventiveness. Its chefs have created three original recipes, based on experiments proving that adding Formica rufa ants to milk triggers its coagulation. There are no limits here: live, frozen, or dehydrated ants are all included in the pot.

As proof, the ant-wich : an ice cream made from sheep's milk yogurt, fermented by live ants as a starter. This ice cream was sandwiched between an ant-infused gel and crispy tuiles, the whole thing cut into the shape of an ant using a laser stencil. The ants bring a strong, tangy acidity that contrasts with the richness of the milk, while a serving temperature of -11°C helps balance this unusual dessert.

In the process, the chefs created a goat's milk "mascarpone," with dehydrated ants catalyzing the coagulation process. The result: a texture similar to classic mascarpone, but an intense, aromatic flavor reminiscent of well-aged pecorino.

Finally, they created a milk cocktail inspired by an 18th-century tradition: milk is traditionally curdled with lemon acid. Here, dehydrated ants cause the milk to curdle and separate. The cocktail offers fruity notes (apricot liqueur, brandy with raisins, dried figs, caramelized apples) and a silky texture thanks to the residual whey in the milk. Replacing the lemon with ants resulted in a milder acidity and a unique flavor, enriched with fruity nuances.

Between culinary innovation and health vigilanceResearchers warn: there's no question of improvising as an entomologist chef in your kitchen, unless you're a seasoned food microbiologist. Why? Because living ants can harbor an unwanted stowaway: the parasite Dicrocoelium dendriticum , which causes hepatic fluke disease in humans. While the risk of infection remains low, this small worm, 5 to 15 mm long, can colonize the gallbladder and bile ducts, causing bile duct irritation, infectious hepatitis, liver pain, diarrhea, anemia, and constipation.

In culinary experiments, live ants were ground up and mixed with a little milk, before being filtered through a fine mesh to eliminate any parasites, while allowing bacteria and yeast to pass through into the fermentation medium. Freezing is another validated method for killing the parasite. Be careful, however: freezing followed by a long incubation at high temperatures, such as those required for fermentation, can promote the appearance of pathogenic microbes, particularly the dreaded Bacillus.

Final warning: to date, ants are not on the list of insects officially authorized for human consumption in Europe, according to Regulation 2015/2283 on novel foods.

Scientifically exploring the rationale behind an ancestral practiceLet's now return to the study published in iScience, which sheds light on how the ant's holobiont—in other words, the insect and the bacteria it hosts—can initiate milk fermentation. The researchers wanted to test whether this inseparable tandem, ant and microbes, was capable of providing the acids and enzymes required to transform milk into yogurt.

To understand this phenomenon, the team looked at red ants (Formica rufa) used as natural leaven, drawing on ethnographic evidence and current culinary experiments.

A brief historical detour is in order: yogurt, this fermented milk so particular in its acidity and texture, is the fruit of complex relationships between humans, animals, microbes and even the environment. It is the microbes which, by "colonizing" the milk, trigger through their enzymatic processes the transformation into a sour and creamy yogurt. This interspecies alliance is found in the Turkish term for sourdough: "maya" .

At the beginning of the 20th century, two famous microbiologists, Stamen Grigorov and Ilya Metchnikoff, isolated Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus from Bulgarian "maya", paving the way for industrial yogurt, which was standardized and much less rich in biodiversity.

Long before the industrial era and the advent of standardized bacterial strains, plant materials were used to aid milk fermentation: chamomile flowers, linden flowers, or nettle roots, particularly in Turkey and elsewhere. This practice of starting the first yogurt is found throughout the Balkans. In Turkey, it is often with adult ants, their eggs, larvae, pupae, or nest material that is used.

Holobiont or how the ant and its microbes make moneyThe researchers hypothesized that the ant's holobiont could provide the acids needed for fermentation. To test this idea, they made experimental yogurts using live, frozen, or dehydrated ants.

Adding live ants to fresh milk introduced lactic acid bacteria, which multiplied during fermentation. Quantitative PCR analyses confirmed this proliferation, while molecular biology techniques identified the viable bacteria present in the yogurt.

Several species of lactic acid bacteria were cultivated in yogurts made from live ants. Among them, Fructilactobacillus sanfranciscensis was isolated, a bacterium not only associated with ants but also known for its role in the fermentation of sourdough bread. These yogurts exhibited a rich and stable microbiota, dominated by lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria.

In contrast, yogurts made with frozen or dehydrated ants showed variable bacterial diversity and the possible presence of Bacillaceae , a family of spore-forming bacteria. In these yogurts, Bacillaceae dominated, while they were absent or almost non-existent in yogurts made with live ants. Several species were isolated, including Bacillus cereus , a known food contaminant. Although the observed quantity is not sufficient to declare these yogurts unfit, their presence indicates a potential risk.

In short, the microbiota of dead ants (whether frozen or dried), unlike that of living ants, does not have the talent required to serve as a leaven for the fermentation of yogurt.

Milk Acidification: When Ants and Bacteria Combine Their TalentsResearchers have shown that the transformation of milk into yogurt relies on a true synergy between ants and bacteria. In a conventional yogurt, it is the bacteria that metabolize lactose, producing mainly lactic acid, but also smaller amounts of acetic and formic acids. These acids are essential: they give the yogurt its tangy taste, its thick texture, and ensure its preservation. However, ants of the genus Formica have a venom gland very rich in formic acid, which can represent up to 10% of their weight! The study reveals that this formic acid is the most abundant acid in yogurts obtained from ants, diffusing into the milk and influencing the product's tangy profile and specific texture.

In addition to formic acid, analyses detected lactic and acetic acid in the ant-based yogurts, proving that bacteria associated with ants play a major role. These two acids are more concentrated in yogurts made with live ants than in those made from dehydrated or frozen insects. Their production varies depending on the season and the diversity of bacteria: the highest concentrations are in spring.

It is worth noting that these ant yogurts are less acidic and contain fewer bacteria than their conventional or homemade cousins: 2.5 g/L of total acids compared to up to 12 g/L in commercial yogurts, with a pH of 5.0–5.9 compared to 4.2 for supermarket yogurt.

Ants and bacteria provide enzymes that influence the texture of yogurtThe study also showed that the ant holobiont also provides enzymes, including proteases, capable of modifying the texture of yogurt. These enzymes break down casein, the main protein in milk, and make the result firmer or more fluid.

Proteomic analysis confirmed that the ant holobiont does indeed contribute to protease production during fermentation. Several ant-derived proteases have been identified, some of which degrade casein. The ant-associated bacterium Fructilactobacillus sanfranciscensis produces two types of proteases, one of which has casein-degrading activity. These enzymes are found in both live and dehydrated ant yogurts.

In summary, this study shows that the various components of the ant's holobiont—the insect itself and its microbial flora—act synergistically. They provide acids and enzymes, and probably other as-yet-unknown substances, that modulate the acidity, milk coagulation, and flavors of yogurt, thus contributing to its unique organoleptic profile.

OutlookFor Veronica Sinotte, Leonie Jahn, and their colleagues at the University of Copenhagen, who led this study, the bacterial diversity associated with ants deserves to be explored in the future in certain key functions of fermentation, such as the transformation of sugars or the production of volatile compounds responsible for aromas. This work suggests the possibility of more finely controlling certain types of fermentation, particularly for sourdough bread or plant-based yogurts.

The authors add that, in the field of modern gastronomy, familiarizing the public with familiar foods made from microbes and insects could change the perception of entomophagy. It remains to be seen whether this type of argument will truly convince consumers. But above all, let's hope that the future of ant-based fermentation does not involve the rampant collection of these insects, because it is important to preserve their already fragile biodiversity.

In short, while ant-fermented yogurt remains primarily a scientific and gastronomic curiosity, it also embodies the legacy of a unique cultural tradition. In some Balkan villages, fermenting yogurt isn't just a matter of patience: it's literally a labor of love.

To find out more:

Sinotte VM, Ramos-Viana V, Vásquez DP, et al. Making yogurt with the ant holobiont uncovers bacteria, acids, and enzymes for food fermentation . iScience. Published online October 3, 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113595

Sirakova SM. Forgotten Stories of Yogurt: Cultivating Multispecies Wisdom . J. Ethnobiol. 43, 250–261. doi:10.1177/02780771231194779

Contribute

Reuse this contentLe Monde