A 15th-century monastery in Segovia reopens to showcase its art and vindicate King Henry IV the Impotent.

A couple of turns of the key and you enter mid-15th-century Segovia. This is the door that gives access to the monastery of San Antonio el Real , which has been closed for four years, ever since the last three Poor Clare nuns who lived in its more than 10,000 square meters and the almost 40,000 for gardening and other tasks had to leave. The nuns obeyed the Vatican rule that requires a monastic community of fewer than five members to leave their place to regroup in another. They had been there for the last 533 years, but said goodbye on June 13, 2021, the feast day of Saint Anthony. Now the Federation of Poor Clare Nuns has ceded it for 30 years to an association, Camino del Asombro , which aims to recover and publicize its artistic and cultural heritage, explains its president, Juan Ayres.

The Gothic-Mudejar monastery, explained Alicia Vallina , PhD in Art History and curator of the State Museums, has been open to visitors in parts since June 13th with a guide and in groups of about 30 people, for seven euros admission. Vallina is in charge of the museography, ensuring that the tours "offer an organized and meaningful account of the monastery that the public can understand, explaining the rooms, and ensuring that the objects tell their story," she added. Work is also underway to make it accessible.

The Castile and León Regional Government has supported the project with a €210,000 grant, plus another €90,000 from the association. “There are just over 2,000 Catholic monasteries worldwide, half of which are in Spain. And of these, half are in Castile and León. In the last 10 years, between 10 and 15 have been abandoned across the country, many of which are of great heritage value,” says Ayres.

However, the property occupied by this building originally had another use. It housed the hunting lodge of the King of Castile , Henry IV (1425-1474), who has gone down in history as "the impotent"—he was unable to consummate his first marriage, to Blanche II of Navarre, when he was 15—and who suffered from health problems. "He was brought here at the age of five, when he was a prince, for his education. It was a place that marked him, and to which he later ordered his two half-siblings, Alfonso and Isabella, the future Catholic queen, to be brought."

Henry IV reigned from 1454 until his death 20 years later. He was fond of music, literature, and hunting in the woods, but less so of government affairs in an age of intrigue and betrayal. The monarch donated the pavilion to the Franciscans to create a convent. However, in 1488, his half-sister Isabel, now queen, invited this more quarrelsome order to leave and gave the place to the Poor Clares for a contemplative life, as evidenced by the grilles of the parlors at the entrance, from which the nuns communicated with their loved ones when they visited.

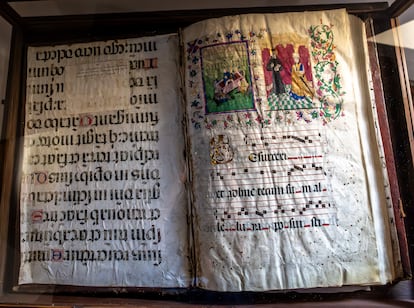

The tour begins with a modern portrait of Henry IV, painted this year by painter and illustrator Fernando Vicente, to give visitors a sense of the character. “I painted it based on existing documentation about him, a small portrait of him discovered in a monastery hymn book, and the better-known one, with a red cap, found in a codex in Stuttgart,” Vicente says over the phone. “Actually, there is no known image of him, except for some 19th-century paintings that are more fantasy-like.”

The illuminated hymn book, part of the monastery's collection, dates from the second half of the 15th century. It contains the unfinished miniature of the king that Ferdinand Vincent used for his portrait, in which he is shown "kneeling before Saint Anthony of Padua, to whom he had great devotion, seeking his blessing." "He is in a prayerful attitude, with a sword and crown, and wearing a Mudejar-influenced costume," notes Vallina.

And, as explained on a panel, his face "matches the chroniclers' descriptions: large head, powerful chin, flattened nose, large dark eyes, and a furrowed brow." Vicente hopes this project will also serve to "vindicate" a monarch whose successors, the Catholic Monarchs, spread an image that eventually became a dark legend.

“We are in the monarchical area of the monastery,” Ayres announces. In one room are some musical instruments, among which “an 18th-century English piano” stands out. After leaving the choir books, the tour continues through what were the chambers of the king and his second wife, the Portuguese Juana de Avis, his cousin with whom he had a daughter. His first marriage had been annulled.

The library books and documents of San Antonio el Real must tell different stories. The latter are located in a chest of drawers bearing the following inscription: "Archive of the papers, titles of ownership, annuities, and privileges of this convent. Year 1766."

Entering the "monastic part," there is an "open garden" where vegetation has taken over the space. Another objective is "to recover the green areas, because botanical knowledge was preserved there," Vallina notes.

Around the central cloister, a "hostel of silence" is planned, says Ayres, "a refuge for reflection and silence" among walnut and chestnut trees, which will adapt some of the more than 100 cells of different stages throughout the monastery.

The visit reaches the most artistically valuable part, the coffered ceilings, which "have been preserved free of woodworm, largely thanks to the nuns' patient cleaning of them with homemade equipment," a feather duster tied to a long reed. It should be noted that some of these ceilings are more than 10 meters high.

“The quality of these coffered ceilings is magnificent,” says Enrique Nuere, architect and member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts , a leading expert in what is technically called “loop carpentry.” Nuere recalls that these ceilings were renovated at the end of the last century and that when they were built, “they were expensive, a distinctive element.” He also clarifies that although they are called “Mudejar coffered ceilings,” they are not actually that. A scholar of Islamic architecture, “where ceilings were flat,” he points out that coffered ceilings are a construction system that “was based on what was done in Germany and England.”

Nuere highlights the church's coffered ceiling, "which is not only decorative but also structural"; the coffered ceiling of the chapter house, "which is an octagonal floor plan within a square and supports the floor above it," and the ceiling of the cloister's arcades, which features a mesmerizing decoration with eight-pointed stars. It symbolizes the sky with its infinite stars, which is why nuns who died in the convent were buried at its feet, explains Ayres. Another plan is crowdfunding so that these stars can be sponsored and the patron can see their name written on them in a digital application.

In the monastery church, whose Gothic-Isabelline façade is by the French architect Juan Guas —who developed his work in Spain—you can admire the beautiful figures from a 15th-century Flemish altarpiece, in polychrome wood, depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ. These figures were removed from the main altar and tightly placed in a niche. This, at least, allows us to see the delicate expressiveness of their faces up close.

In the refectory, the president of Camino del Asombro describes how the nuns ate lunch. There was a U-shaped table where the hot pot was placed. It was served first to the abbess, who tapped her spoon on the table; this signaled the nuns to open the lockers with wooden doors behind them and retrieve their cutlery and plates. This scene is intended to be shown "in augmented reality to visitors."

Another trace of the nuns who lived here are the straw hats they wore when working in the garden. These hats are hung on a coat rack with name tags glued on them so they could always wear theirs: Asunción, Isabel, Catalina...

Finally, in a large room on the upper floor of the building, objects found in various rooms are collected, such as the lidless coffin used to hold wakes for the nuns when they died, dated 1766, according to a small plaque. Also present are the novices' trunks when they entered the convent, and a small relic measuring one square centimeter of Jesus's skirt—with its certificate of authenticity from the Vatican—which belonged to Isabella the Catholic and was left to the monastery in her will, Ayres notes.

EL PAÍS