The war ended on May 7th: Did we celebrate wrong for 80 years?

To mark the end of the war in Europe, the Allied Museum in Dahlem is presenting an exhibition that sheds new light on Germany's surrender in 1945. The exhibition is apparently connected to current efforts to shed light on the actual course of the surrender: It aims to clarify that Germany did not surrender to the Soviets in Karlshorst on May 8, 1945, but rather on May 7 in Reims, France.

Signing before Eisenhower's representatives in Reims

In the middle of the night, on May 7, 1945, at 2:41 a.m., in the map room on the first floor of a former school in Reims, the unconditional surrender of the German armed forces took place. According to the French Ministry of Defense, the school was the command center of General Dwight Eisenhower and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF). Colonel General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Wehrmacht General Staff, had been brought to Reims on behalf of the Germans. General Walter Bedell-Smith, Chief of Staff of the SHAEF, signed the surrender document on behalf of the Western Allies. Next, Soviet General Ivan Sousloparov signed on behalf of the Red Army, and finally, French General François Sevez, Deputy Chief of the General Staff for National Defense, was asked to countersign the document in his capacity as a simple witness, since the event was taking place on French soil. Alfred Jodl signed on behalf of the armed forces of the Third Reich. Eisenhower, who holds a higher rank than Jodl, did not attend the signing ceremony. However, he received the German delegation in his office afterward, followed by the press and his staff, with whom he toasted with a glass of champagne before delivering his famous victory speech.

Stalin insists on Karlshorst

Marc Hansen, political scientist and military historian from Kiel, explained the significance of the ceremony at the opening of the exhibition on Tuesday evening: "The Soviet representative at SHAEF, Colonel General Ivan Susloparov, had to accept the surrender from the USSR without concrete approval from the Soviet High Command. His request for timely provision of the relevant directives fell on deaf ears in Moscow. And this was probably not entirely unintentional. After all, Stalin subsequently declared that he would accept the Reims Act – but only subject to the requirement that the act of surrender be repeated – under formal Soviet control." The Wehrmacht was therefore forced to surrender once again: on May 9, at 12:16 a.m., the second unconditional surrender was signed in Berlin-Karlshorst.

Hansen said in Dahlem: "The end of the Second World War in Europe in May 1945 did not mark the beginning of a peaceful postwar order, but rather the starting point for the rapidly developing systemic conflict between West and East. From the outset, the anti-Hitler coalition of the USA, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and France was not an ideologically homogeneous community, but rather an alliance of convenience against a common external enemy—Nazi Germany. With its military defeat, this alliance fell apart. The political reality from the spring of 1945 onward was therefore not characterized by cooperation, but by the beginnings of competition."

Confrontation right from the start

Hansen said that the Reims and Karlshorst surrenders, and the way they were handled by the victorious powers, "thus marked not only the end of the war, but also the beginning of a new era of geopolitical confrontation." Immediately after the war, the Western Allies pursued a relatively unified "victorious powers narrative," which emphasized "that the Axis powers were defeated together." In the United States and Great Britain, however, the Reims surrender was "increasingly emphasized over time to underscore the leadership role of the Western Allies in ending the war."

Hansen continued: "They largely accepted the Soviet interpretation of Karlshorst in order not to jeopardize the USSR's claim to prestige—a political decision in the spirit of cooperation in occupied Germany." Hansen added: "In this context, Western culture of remembrance focused on the military victories in Normandy, the advance of the Western Allies, and the liberation of Western Europe."

France, which was not formally involved in the Reims capitulation, even benefited from the Karlshorst staging, as it appeared as an equal actor.

Soviets deliver better staging

As the Cold War progressed, however, the former Allies began to "increasingly use the memory of the capitulations for their own political purposes": While Karlshorst "continued to be portrayed in the Soviet bloc as the only true capitulation, the USA and the Western European victorious powers increasingly used Reims as their capitulation narrative."

But according to Hansen, the transport of historical images has prevailed: "The almost exclusive imagery from Karlshorst has significantly shaped our collective image of the 'end of the Second World War' – while Reims, although legally first and equally valid, is barely present. Because – only the images from Karlshorst developed into visual icons of the surrender – initiated and supported by a targeted Soviet image policy."

According to Hansen, this image policy included, above all, the perfect staging of the surrender in Karlshorst: "In Karlshorst, everything was done to create an effective image arrangement for the purposes of memory politics: the location—an officers' mess—the lighting conditions, the camera-effective staging of the act." Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, in particular, was deliberately chosen, even though he held no operational military function. His appearance established him as the "virtually perfect symbolic figure of declining German militarism": "His monocle, his stooped posture due to his height, the scene of the signing became an icon of German subjugation. It was no coincidence that Soviet image propaganda placed him at the center, and not Dönitz or Jodl."

Only logical: No Russians at the commemoration

The Soviet leadership ensured photographic and filmic documentation, which was deliberately disseminated internationally. Karlshorst thus became not only the 'second' surrender site, but also the visual memorial – a staging of the Soviet Union's victorious role as the decisive force in the liberation of Europe.

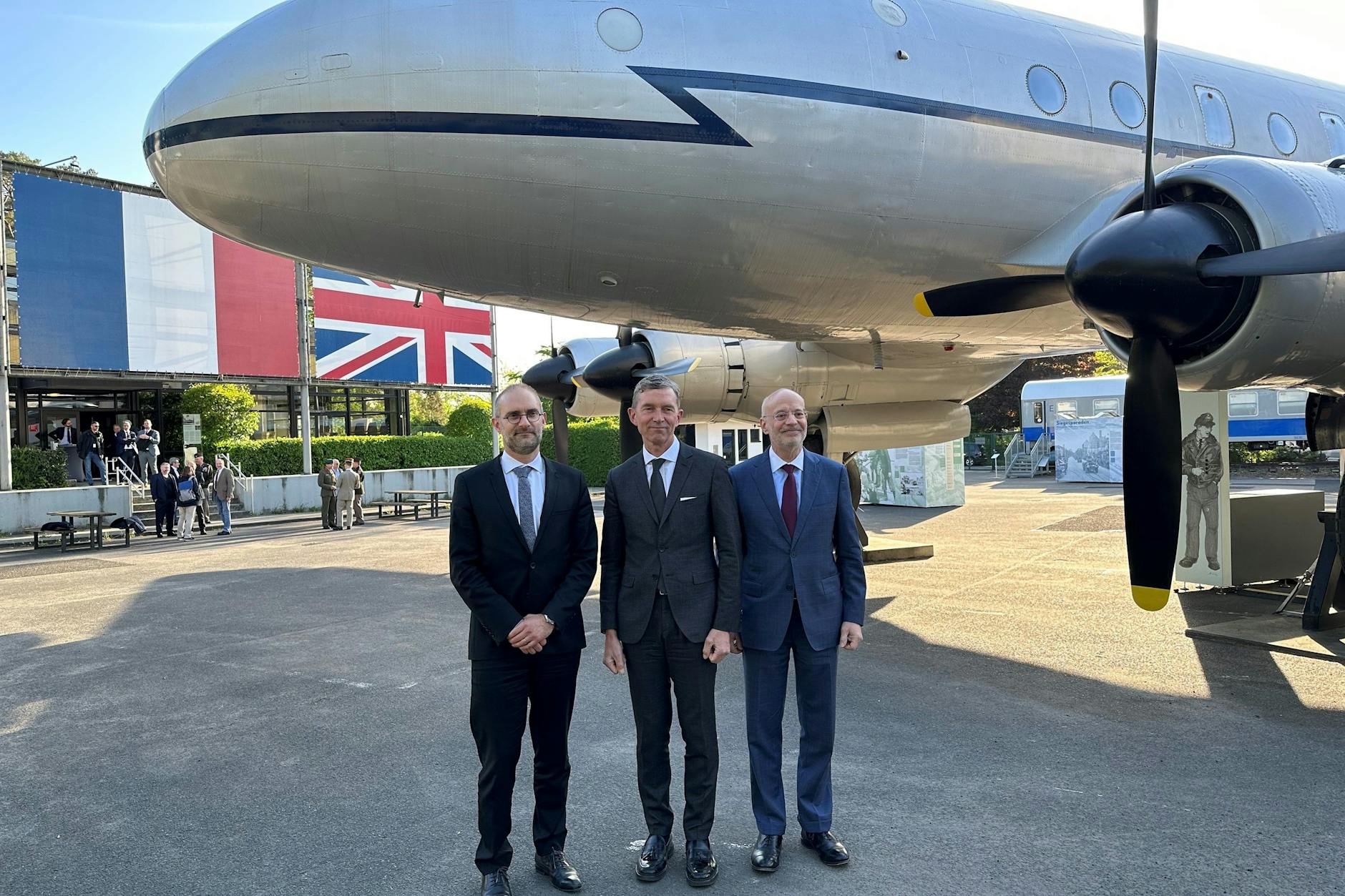

The opening of the exhibition at the Allied Museum was attended by the US Chargé d'Affaires in Germany, Alan Meltzer, British Ambassador Andrew Mitchell, and French Minister Emmanuel Suquet. A Russian representative was not invited.

US Charge d'Affaires calls for more money for defense

Meltzer said that reconstruction and reconciliation are "incomplete without a meaningful resolve to carry us forward." This resolve includes "a clear commitment to defend what we and our allies have built together." He added that several million Americans fought alongside other allies in Europe "to overthrow fascism and tyranny." Meltzer continued: "If the past teaches us anything, it is that we can only repel aggression through strength." As the Trump administration has made clear, "all NATO allies are called upon at this moment to do more to share the burden of our common defense," Meltzer said.

Allied Museum Director Jürgen Lillteicher said that Russia had "destroyed the European peace order" with its attack on Ukraine. Therefore, "a joint commemoration with Russia is unfortunately not possible." Peace is not in sight, he added, and the Russian attack and the rise of "right-wing extremist forces" in Europe underscore the "enormous importance" NATO has today.

There are currently several efforts underway to educate the West about the significance of Reims. For example, filmmaker Wim Wenders, funded by the German Foreign Ministry, made a four-minute film. The film aims to shed light on the significance of Reims as a counter-narrative to the Soviet interpretation, thus bringing it to the attention of future generations:

Berliner-zeitung