Poststructuralism | Walking on thin ice

In a conversation in an apartment in the old west of Berlin, Hans-Jörg Rheinberger and Hanns Zischler describe how their reading of Jacques Derrida's "De la Grammatologie" a good 50 years ago culminated in a process of translation. Their approach to language resembled a "linguistic cardiogram": they listened to each word individually for all their possible meanings. They wrote the work together, using a portable typewriter, starting in the fall of 1969. Five years later, at the end of November 1974, "Grammatologie" was published in German. In June 1975, the "Süddeutsche Zeitung" published Lothar Baier's review, which finally made Derrida's book common knowledge in Germany.

A 1968 storyThe perpetrator returns to the crime scene, so they say – and that means that when you look for the perpetrator in his home, he is sometimes not there. When we arrive at Hanns Zischler's apartment in Berlin's Westend, we find ourselves in front of a locked door because, whether by misunderstanding or by automatism, Zischler has returned to the scene of the project we will discuss below. So we follow the "perpetrator" to the "crime scene," which is on Knesebeckstrasse, right next to the house where Hans-Jörg Rheinberger lives today. Back then, in the 1960s and 70s, he lived one house down, with seven other roommates, in an apartment the same size as the one he currently lives in alone with his wife. There he met with Hanns Zischler to translate. The two of them worked on a typewriter—a portable typewriter, to be precise.

As a child, Hanns Zischler recounts that he once fell through the ice at a massive dining table converted into a desk on Knesebeckstrasse. The child's misunderstanding: He didn't turn around and return to dry land, but simply kept going. He repeatedly fell through the ice, yet kept moving forward – seeking support in the material that was evaporating beneath his feet, or at least enjoying the lack of support. Back then, in the 1960s and 1970s, reading Derrida – and then translating it, too – was just as supportless. Rheinberger and Zischler call this principle "learning by learning" and describe how the reading of a work that can today be called a standard work of "deconstruction" culminated in the process of translation.

The university, as Zischler and Rheinberger describe it, was then a place of listening, of radical listening. People had time – this is perhaps the most striking difference from today, at first glance, and one that quickly becomes apparent. Three generations, all of whom studied in different ways and experienced the city in the process, are sitting at this dining table that has been converted into a desk.

Between theory and literature"Derrida doesn't abandon us, he is reliable," repeats Hanns Zischler, not only confirming the lasting impact of immersing himself in Derrida's language. Perhaps he is also performatively depicting exactly where the thin ice that one could not leave had formed: on the surface of language, no, even of writing. Derrida is reliable because he makes the world of words seem unreliable—and this unreliability is invigorating, moving, a thankfully impossible, endless project. Perhaps this is the reason why Rheinberger and Zischler repeatedly ponder what it would be like to tackle the "Grammatology" project once more, to produce a second, a new, a contemporary (and soon again historical) new translation fifty years later. For Derrida, the reckoning of time, the narrative of life and knowledge, of science, cannot be understood in a linear way. He does not understand time as a sequence of nows, since past, present and future overlap in constant shifts and references through postponement and advancement of meaning.

Viewing language as something fluid is entirely in the spirit of Derrida, who transforms one's own mother tongue into a foreign language, especially in the special remote proximity that arises in the act of translation. This is just one aspect of the still elusive project of so-called deconstruction, which lies at the interface between literature and theory. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Derrida began his writing career by translating a short text by the philosopher Edmund Husserl: Translation is a distinct, albeit underrepresented, art form. An art form that takes as its basis the affirmation of the gap between the sign and what it signifies. It is, in and of itself, walking on thin ice; it is always interpretation, authorship, and never merely an achievement in the service of language. It means devoting oneself entirely to something that does not yet exist: the thin ice of writing that one creates, translating. One saves oneself with, through, and on the material that abandons and lets one down, precisely because it represents uncertainty—an uncertainty that lures, that seduces, that haunts. Because, again: "Derrida is reliable; he never abandons one." Translating Derrida means getting to know one's (own) language anew; a paradigm shift that is as personal as it is universal.

Fundamental doubts about the systemPerhaps this shift is paradigmatic of the time, those 1970s in Berlin, when Konrad Adenauer's post-war era, the forgetting and repression of the Nazi era, were finally being questioned, and at the Free University of Berlin – the world in which the two translators Zischler/Rheinberger lived – self-efficacy in the seminar room replaced listening in the lecture hall: "In 1968," Hans-Jörg Rheinberger recalls, "self-organized reading began in independent student working groups. That was a completely new way of working." But this shift is also specific to the work "Grammatology," which tends to disturb and unsettle rather than systematize and explain. And for the fact that the two translators had only partially read the work to which they were devoting themselves so intensively at the time. Groping, listening, empathizing, they devoted themselves, word by word, sentence by sentence, to the unknown. Rheinberger describes this as thinking with their hands. Insights that emerge from the typing, searching fingers on the typewriter. The stethoscope is placed over the words, and doubt about what is heard and how it should be interpreted is the constant companion of the two translators in their work – fortunately. For fundamental doubt about systems and worldviews is also the basis of Derrida's theory, which radically undermines all systems of judgment. The two call it "invigorating skepticism," and indeed, that's what it is for us listeners as well.

One can read Derrida's "Grammatology" as much as an early media theory as a treatise on time. Our encounter on Knesebeckstrasse is both a meditation on time and a brief journey through time. We are touching upon a time in which linguistics is the object of study, in which the study of language functions neither as an image nor as a speech act, but rather as a search for traces, perhaps also in the context of the unease with authority that characterizes the second half of the twentieth century. Layered traces of history and meaning, superimposed.

Gramma – that means "trace" in ancient Greek. At this dining table, which has been redefined as a desk, we glimpse, we experience traces of a time when seven people lived in an old apartment on Knesebeckstrasse, when people studied for decades, when they studied in depth rather than breadth. It was a time when students wanted to lose themselves instead of becoming more efficient, wanted to experiment between disciplines – like Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, meandering between Althusser and a rigorous biology degree, and Zischler, already halfway into theater practice. In those days, people wanted to unlearn instead of learning – or if they were going to learn, then learn endlessly.

"Derrida was never a school-building subject—the absence of a doctrinal structure is programmatic," says Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, a historian of science who devotes himself to experimentation, experimental design, the vague stage, and still-unwritten history(ies), always exploring the materiality of the research object. "Grammatology opened up a completely new form of reading. It is a book of the century without thereby founding a science, a simultaneous subversion and transcendence of what is received as science." In engaging with it, in reading, one becomes a co-writer. In this case, it is always also a dialogue, or a conversation—with the absent Derrida, with the French language, with the mother tongue that has become alien (and already highly charged, to be viewed with suspicion), with the then-contemporary medium of the typewriter, with each other, and now also with us, just a single house number away from the "crime scene." We, too, engage and become readers, co-writers. Reading, in Derrida's sense, is also writing, a continuous process of active reflection and conflict, of the postponement of meaning and its deconstruction – just as translation is. The text inscribes itself, as if of its own accord, a paradigm shift, accomplished with gentle persistence. It is reliable, it never abandons us. It meanders on, like a river, fluid, into the present – and is radically historical.

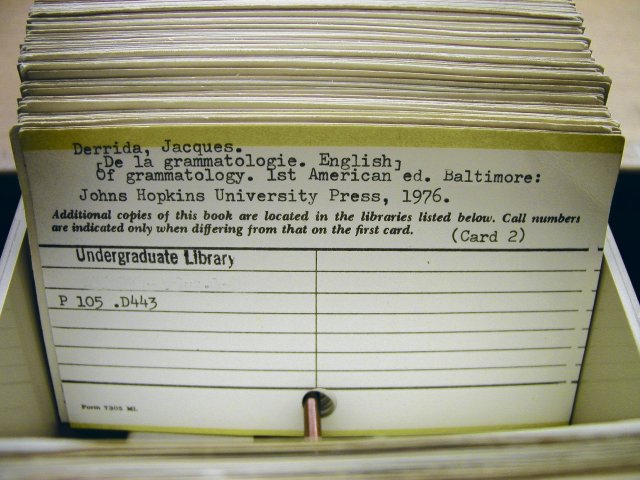

Of gaps and tracesThe trace, the difference, the postponement: concepts that, in Derrida's work, are both programmatic and performative – and yet neither, because in their repetition they simultaneously possess the character of a manifesto, while in this very process of "iteration" themselves blurring, overlapping, differentiating, and postponing their meaning. "The idea of the book, which always refers to a natural totality, is profoundly alien to the meaning of writing," it says in "Grammatology." This movement is omnipresent in the underrepresented art form of translation and, to a certain extent, was also palpable in our encounter on Knesebeckstrasse: in our shared reading of traces, in our attempt to understand one another – and in doing so, happily surrendering to misunderstanding. The difference becomes clear at the latest when Hans-Jörg Rheinberger produces a thick file: These are the original documents of the translation, written with the letters of the portable typewriter, which from today's perspective seem anachronistic, supplemented by handwritten versions of individual words.

All of this is now before us: the affirmation of the gap between sign and signified, revealed in the endless traces of overwriting, whitewash, and deletions in the translation manuscripts, revealing at the same time the radical search for precision; the enigmatic nature of the traces that lie upon one another, the groping with fingertips on the thin ice of language; the impossibility of distinguishing the "inside" from the "outside," the style of "engaging" for the sake of engaging, which is nevertheless, or precisely because of this, political; the provocative openness of a still unwritten system of thought with gentle persistence, undermining systems of judgment without introducing new ones. Collaborative writing as shared navigation on thin ice; writing, reading, and translating as indistinguishable forms of movement. the tyranny of letters, the barbs of language, the poetic that becomes theory (and vice versa), non-linear narration as we know it from vague memory, the text that writes itself, that inscribes itself; the great maybe that we took the time to write fifty years ago. All of this now lies before us, in the form of actual writing on actual paper. Paper about whose nature and meaning Derrida wrote a 60-page essay, devoted to a deepening that always remains a bit futile. One writes, one speaks, because there always remains a gap, a misunderstanding, fortunately. Not despite this, but because of this, Zischler says: "Derrida is reliable, he never abandons you."

But what do the perpetrators, the repeat perpetrators of "grammatology," have to answer for? Perhaps first and foremost, the profound influence they have had on us by anchoring so-called deconstruction at the margins of the canon. Even if we are not Derrida experts, our language is nevertheless permeated by his historical presence, the postponement, the gap, and its lasting consequence. The concepts of postponement and deconstruction have long since entered our everyday vocabulary, and when Hans-Jörg Rheinberger speaks of Derrida's influence on his hard science of biology, the idea of the nonlinear reappears in new terms: "Even in experiments, one thing is layered upon another, generating recursions, feedback loops, and other unexpected effects." History is not written linearly; traces lie one upon another and on top of one another, in heterogeneous unity, in a timeless presence, stored in language. Last but not least, the voices of the two translators, who have gathered with us at the converted dining table, remain present.

In 1976, two years after the publication of "Grammatology" in German, Wim Wenders' film "Im Lauf der Zeit" premiered, starring Hanns Zischler. Zischler is a hybrid, a theorist as well as a theater person and writer, just as Derrida's works themselves are hybrid. The protagonist, portrayed and embodied by Zischler, daringly drives a VW Beetle into the Elbe River – only to then emerge from the water, appearing somewhat unconcerned. It is both a suicide attempt and an attempt to test and challenge the seemingly self-evident givens. A daring, radically vivid suicide attempt, a testing of the element of water in its fluidity. Nothing is self-evident; everything must be experienced, embodied. The distance from the role one plays in social space is always present; one hovers a meter above the water, above the words, above one's own identity. One walks on thin ice – not despite, but because one cannot trust it.

The author conducted the interview with Hanns Zischler and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger together with the journalist Fritz von Klinggräff.

nd-aktuell